Amie, a young British woman who had spent years contributing to the National Health Service (NHS), finally reached a breaking point in late 2025. Plagued by a chronic illness that left her feeling "unheard" and facing a minimum two-week wait just for a GP appointment, she made a decision that many would find radical: she booked a flight to Beijing.

"It sounds ridiculous," Amie shared in a video that quickly went viral, "but in the time it takes to see a specialist in the UK, I could fly to the Far East, undergo an endoscopy, get my results, and start a treatment plan". Her story is a high-profile example of a growing trend: medical tourists from the West seeking the efficiency and innovation of a system that once seemed worlds away.

Amie’s experience mirrors that of many international patients who find the speed of Chinese healthcare "surreal". At premier institutions like Peking Union Medical College Hospital, the process is streamlined to a degree rarely seen in the West. For a deposit of roughly 200 RMB ($28 USD), patients can often see a specialist and complete a battery of blood panels, ECGs, and ultrasounds—all within a single morning.

This efficiency isn't limited to diagnostics. In 2024, a Swedish family traveled to Guangzhou to seek treatment for their two-year-old daughter suffering from metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD). While options in the West were limited or prohibitively expensive, they accessed gene-modified stem cell therapy for 88,000 yuan (approx. $12,000 USD), which successfully halted her neurological decline.

These sagas inevitably lead us to the ultimate question: why does western healthcare cost more-and often wait longer-than their Chinese counterpart?

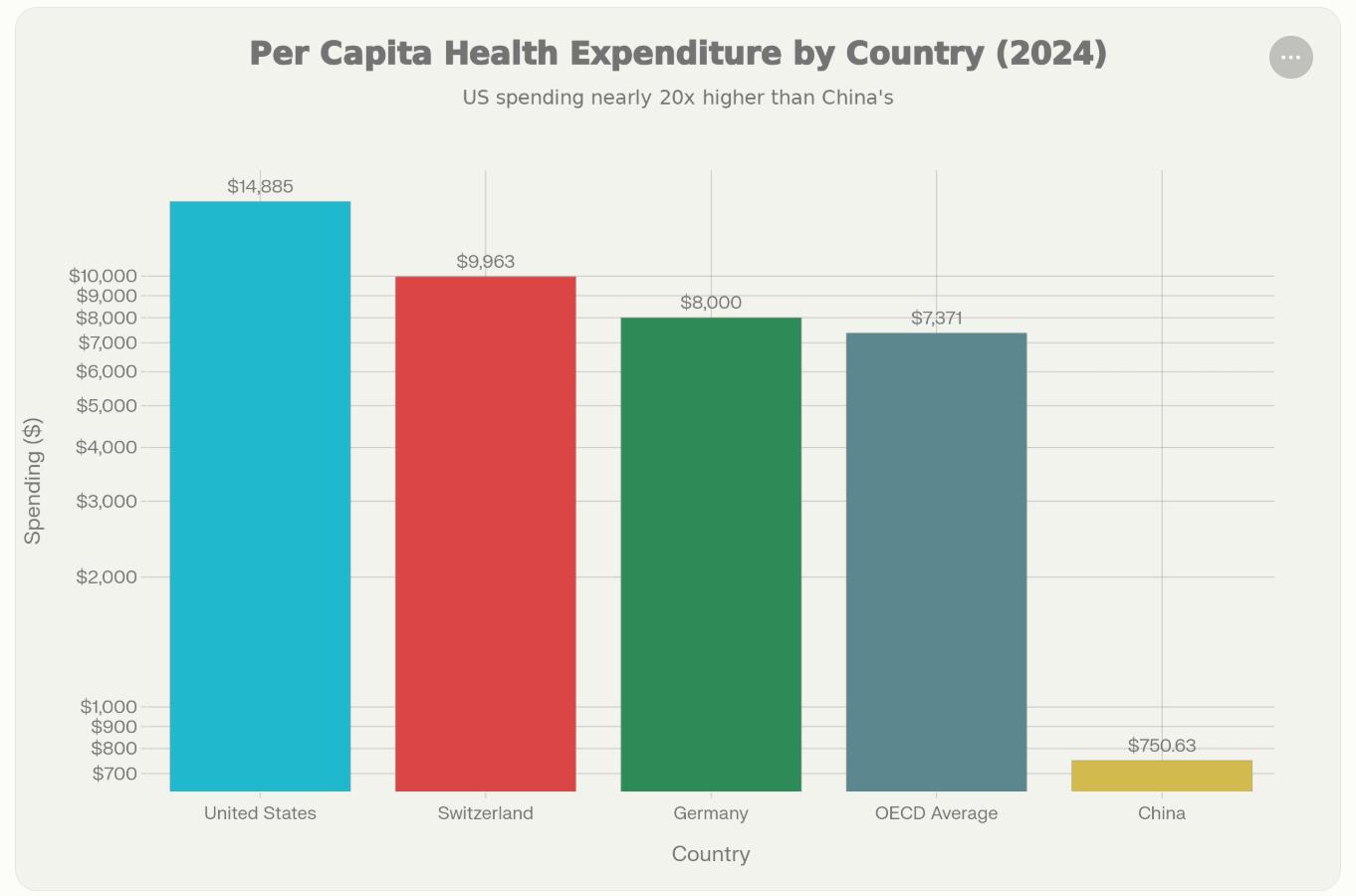

Western healthcare systems, such as that of the United States, operate at fundamentally different cost levels than China. The U.S. spends approximately $14,885 per capita annually on healthcare—nearly 20 times what China spends at approximately $751 per capita. Even Switzerland, the second-most expensive OECD country, spends only $9,963 per capita, while the OECD average (excluding the U.S.) stands at $7,371. This massive cost gap exists despite the U.S. producing worse long-term health outcomes than comparable wealthy nations.

1. Service Delivery Pricing

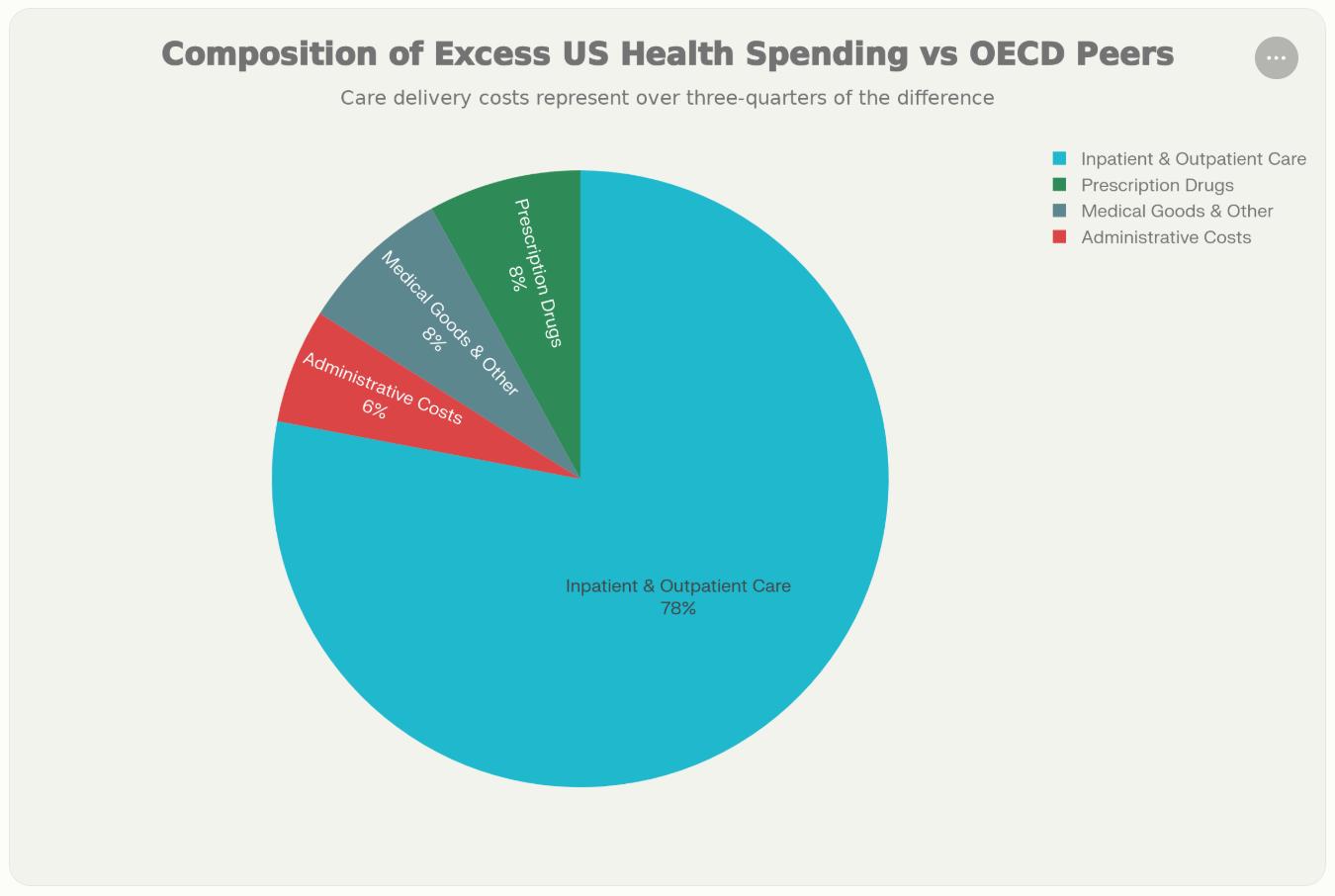

The largest driver of elevated Western healthcare spending is the price of clinical services themselves. Approximately 78% of excess U.S. spending compared to OECD peers comes from higher-priced inpatient and outpatient care services. Physician consultations in the U.S. cost roughly three times more than in other G7 countries, while specialist care is approximately twice as expensive. This reflects both higher physician compensation (U.S. GPs earn $218,000 annually versus significantly less in peer nations) and markup structures on hospital services.

2. Administrative Bloat

The fragmented structure of Wester-particularly American-healthcare systems creates immense administrative overhead. The U.S. spends $1,055 per capita on administrative costs, a figure five times higher than Germany ($306 per capita). Overall, administrative spending accounts for 8% of U.S. health expenditure and represents an estimated $248-$350 billion in excess costs annually. This fragmentation stems from multiple competing insurance payers, complex billing systems, prior authorization requirements, and duplicative administrative functions across thousands of independent healthcare organizations.

3. Pharmaceutical Price Differential

It’s how capitalism works. The U.S. allows higher monopoly pricing for brand-name drugs than other developed countries. Unlike most OECD nations that employ centralized price negotiations and national formularies, the U.S. lacks centralized price-setting mechanisms and permits fragmented negotiations between manufacturers and individual payers. For example, the U.S. discounted price for a common rheumatoid arthritis drug was $2,505 per month—more than double the average price in other high-income countries.

4. System Fragmentation

Western healthcare systems, especially in the U.S., consist of independent hospitals, clinics, insurance companies, and providers with misaligned incentives and minimal coordination. This fragmentation causes inefficient resource allocation, duplicative services, and higher administrative burden. Evidence suggests that integrated healthcare systems (such as Kaiser Permanente) achieve 28% lower resource use than fragmented fee-for-service systems while maintaining equivalent outcomes.

China operates a fundamentally different system architecture that constrains costs through centralized control and low provider-to-patient ratios. The Chinese system is structured on a tiered model (primary→secondary→tertiary care) with centralized government procurement power, enabling price negotiation for pharmaceuticals and medical equipment. Hospitals receive payment through a combination of fee-for-service, diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), capitation, and global budgets—mechanisms designed to align incentives and control spending. Critically, Chinese healthcare workers operate under intense volume pressures: specialists may see 40-50 patients per half-day, with surgeries scheduled late into evening hours to reduce patient waits.

“China’s centralized procurement system has effectively eliminated unnecessary markups in medical pricing,”noted an official from the National Healthcare Security Administration. “Meanwhile, government investment has been substantial. In 2024, total national health expenditure reached nearly ¥9.1 trillion (1.3 trillion USD), with ¥2.26 trillion (322 billion USD) funded by the state.”

China's per capita health expenditure of $751 (2024) reflects this model's efficiency in containing formal healthcare costs. However, this comes with trade-offs: out-of-pocket spending currently comprises 26.89% of total health expenditure (compared to lower levels in universal systems), and doctor workload and patient communication time are substantially constrained.

China’s healthcare model is currently navigating a complex transition as it attempts to balance widespread accessibility with the financial sustainability of its workforce. The macro-level efficiency of the system is increasingly linked to rigorous cost-management protocols within public hospitals, which have led to significant adjustments in compensation structures for medical staff. In 2024 and 2025, many institutions shifted away from high performance-based bonuses to address broader fiscal constraints.

This evolving economic landscape, combined with the high-intensity nature of clinical work in a high-volume system, has created notable challenges for long-term staff retention. As a result, the medical labor market is seeing a shift, with professionals increasingly exploring roles in the private sector or the pharmaceutical industry to find a more sustainable balance between workload and compensation.

The implementation of centralized procurement policies, specifically Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) and the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL), has been highly effective in lowering the prices of essential medicines and medical devices. While these measures have significantly expanded patient access to treatments, they have also altered the incentives for medical innovation.

The reduction in profit margins for established products means that domestic firms must now operate with leaner budgets for research and development, which can influence the pace of breakthrough discoveries. For international pharmaceutical companies, the focus on standardized, low-cost delivery requires a strategic recalibration of how and when to introduce cutting-edge therapies into the Chinese market, as the pricing environment prioritizes immediate affordability over high-premium investment returns.

This emphasis on affordability is closely integrated with a broader industrial strategy focused on domestic self-reliance, which has enabled the healthcare system to leverage maturing local manufacturing capabilities to achieve significant cost efficiencies.

China’s ascendance in pharmaceutical/medical product value chain also plays a part in drive down the cost. With over 80% of high-value medical consumables now domestically produced, healthcare costs have plummeted. Coronary stents, for instance, saw their average price drop from around ¥13,000 (around 1,857 USD) before centralized procurement to just ¥700 (roughly 100 USD) afterward—a staggering 93% reduction. In 2025, drugs included in national medical insurance negotiations experienced an average price cut of over 60%, with products like Haisco’s dornase alfa slashed from ¥145 to just ¥13.6 (< 2 USD).

The issue of waiting times in Western healthcare systems presents a complex picture, with significant variation both between countries and across different types of medical services. The common assumption that universal healthcare inevitably leads to long waits is an oversimplification that requires closer examination. In the United Kingdom, for example, the median wait for elective, non-urgent surgery currently stands at 13.3 weeks, which is notably longer than the pre-COVID standard of 7.6 weeks, while emergency department wait times average 1 hour and 52 minutes. In contrast, Germany demonstrates much shorter emergency room wait times, averaging just 22 minutes. Canada’s system shows further diversity, where 33% of patients report waiting more than a day for medical advice, and 61% wait over a month to see a specialist. The United States, often held up as a counterpoint to universal systems, actually performs better than Canada in these areas, with 28% of patients waiting more than a day for medical advice and only 27% waiting over a month for specialist care.

These differences challenge the misconception that all universal healthcare systems are plagued by prohibitively long waits. Germany, for instance, successfully combines universal coverage with faster emergency access than most U.S. states. The United Kingdom’s current waiting time crisis appears to stem from specific funding and workforce pressures in the aftermath of the pandemic, rather than being an inherent flaw of universal healthcare systems.

In contrast, China reports emergency department wait times averaging approximately 60 minutes, with same-day or within-week specialist appointment availability in major cities.

The core difference lies not in whether systems provide universal coverage, but in their organizational coherence.

On one hand is the fragmented Western Model: Multiple independent payers, providers, and billing systems with weak coordination create redundancy. Yet this fragmentation also introduces competitive pressures and quality variation.

On the other hand, is the centralized Chinese Model: Government-directed pricing, procurement, and payment mechanisms reduce administrative overhead and enable speed. However, centralization limits local autonomy, can perpetuate inequities across regions, and creates intense provider workload pressures. Research demonstrates that centralization itself—when properly implemented—can achieve 23-61% cost savings through elimination of redundant administrative functions.

"Many people assume that 'affordable' is just a polite word for 'substandard,'" Amie says into the camera, her voice steady and certain. "But my lead surgeon was a specialist from the prestigious Peking Union Medical College Hospital. The surgery wasn't just a success—it was seamless."

Amie’s experience is no longer an outlier. China’s Grade-A tertiary hospitals are rapidly ascending to the forefront of global medicine, particularly in high-stakes fields like cardiovascular health, oncology, and minimally invasive surgery. The international medical community has taken note of several groundbreaking "firsts": Shanghai Changzheng Hospital’s successful 3D-printed total cervical vertebrae replacement and Sichuan University West China Hospital’s world-first biventricular pacemaker placement via the hepatic vein.

As of 2025, 85 hospitals across the Chinese mainland have earned the gold standard of JCI international accreditation. "Chinese healthcare is no longer just catching up; it is aligning with—and in some cases, defining—international standards," explains Wang Fang, Vice President of Shanghai Longhua Hospital. "We aren't just following protocols; we are driving breakthroughs in precision 3D printing and robotic surgery."

The surge of medical tourists seeking care in China is a testament to the system’s growing reputation, but it has also sparked a complex internal debate. "Our premium medical resources are already under immense pressure," notes a Beijing-based physician, speaking on the condition of anonymity. "A massive influx of international patients risks lengthening the wait times for our own citizens."

This pressure has birthed a troubling "gray market." Unscrupulous medical intermediaries have emerged, charging exorbitant fees to help foreign patients "leapfrog" the queue, occupying beds and specialized diagnostic equipment intended for the general public. In 2025, authorities cracked down on several high-profile cases involving foreign nationals using fraudulent employment contracts to illicitly access the national insurance scheme.

To address this, China is pioneering a "dual-track" healthcare model. "We are developing dedicated international medical centers funded by private capital," says a representative from the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission. "These centers offer transparent, premium-tier services for foreign patients, ensuring that the local healthcare ecosystem remains undisturbed and equitable for domestic citizens."

The Hainan Bo’ao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone has become the crown jewel of this new era. By the end of 2025, Lecheng had introduced 531 innovative drugs and medical devices that have yet to hit the broader domestic market.

Through strategic tariff-free policies, import duties on medical equipment have been slashed to approximately 3%, while VAT on life-saving drugs sits at roughly 13%. To date, these tax breaks have saved patients and providers 55.97 million RMB.

The unique strength of China’s healthcare evolution lies in the marriage of 'state-led mobilization' and 'market-driven competition, which is a rare model that manages to optimize quality while aggressively containing costs.

At the conclusion of her journey, Amie stood on the streets of Beijing with a new perspective. "I originally thought Chinese healthcare was backward," she admitted. "Now I understand it’s not just affordable—it’s a world ahead in efficiency".