Scientific Superpower on a Middle-Income Budget: Decoding China’s Unprecedented Rise as a Research Outlier

The traditional paradigm of economic development suggests a linear relationship between a nation’s per capita wealth and its scientific sophistication. Historically, as nations transcend the middle-income threshold, the transition from a labor-intensive economy to a knowledge-based one is characterized by gradual increases in research and development (R&D) intensity, institutional maturation, and a steady rise in high-impact scientific output. However, the trajectory of China in the early 21st century has presented a profound challenge to this developmental orthodoxy.

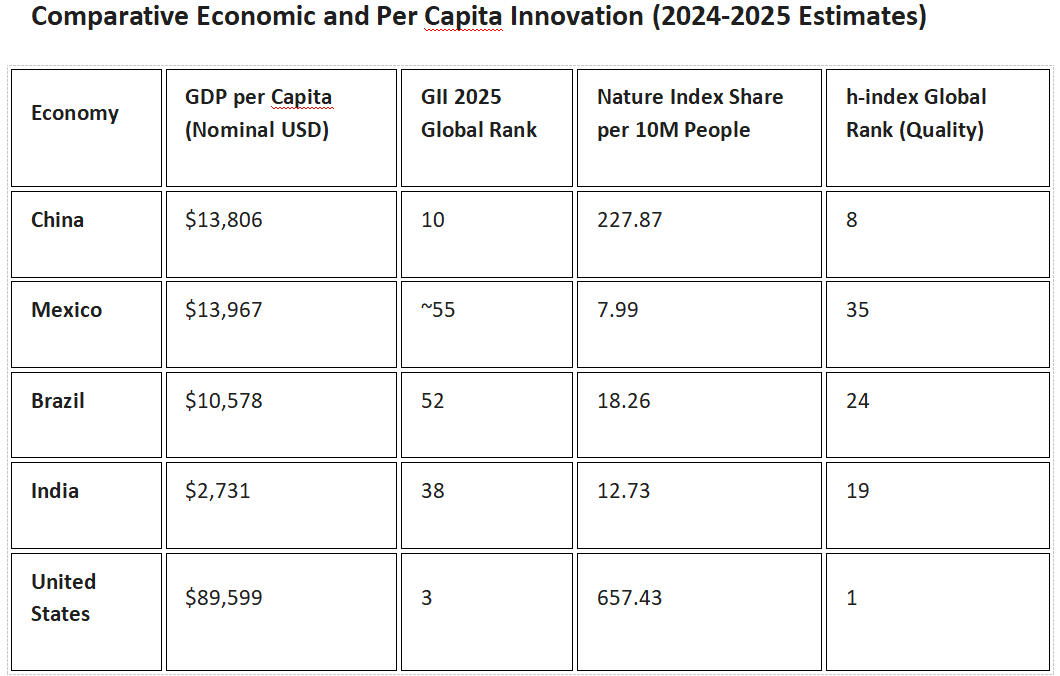

By 2024, China’s per capita GDP stood at approximately 95,749 yuan, or roughly $13,806 at prevailing exchange rates. Despite maintaining an income level that classifies it as an upper-middle-income economy, China has achieved scientific milestones—measured by publication volume, citation impact, and technological leadership—that were previously the exclusive domain of high-income economies with per capita GDPs five to seven times higher.

The Statistical Foundation of the China Outlier Hypothesis

To determine whether China is a scientific outlier, its performance must be contextualized within its economic peer group. When utilizing the Global Innovation Index (GII) 2025 published by WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organization) as a benchmark, the evidence of an anomaly is stark. China ranks 10th among the 139 economies featured in the GII, making it the only middle-income economy to break into the global top 25. This performance indicates that China is an "innovation leader" that significantly overperforms relative to its level of economic development. The GII further reveals that China ranks 1st among the 36 upper-middle-income group economies, reinforcing the notion that its innovative capacity is decoupled from the typical constraints of its income bracket.

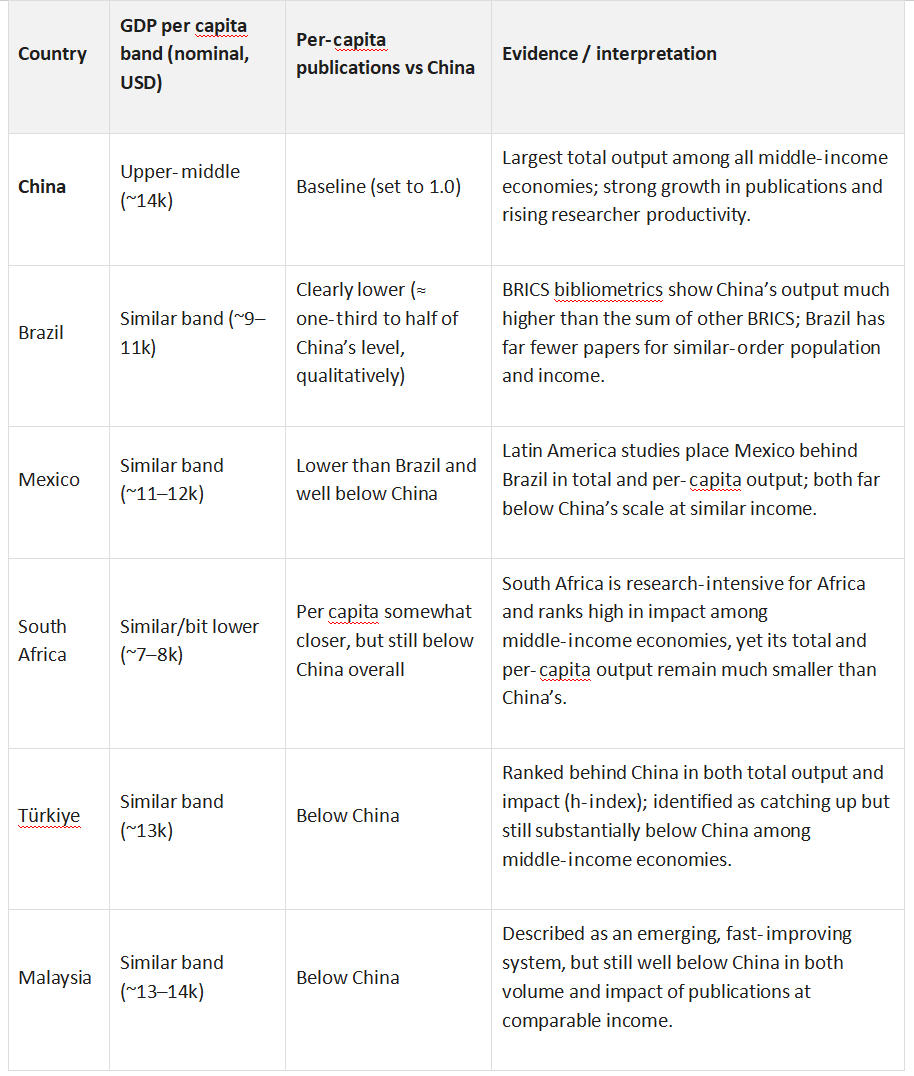

The divergence is most visible when analyzing per capita scientific output. While the United States leads in absolute terms for many metrics, China’s efficiency relative to its income is unprecedented. In fact, China's per capita research output surpasses that of most countries with similar GDP per capita, notably other large upper-middle-income economies like Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and Türkiye. This conclusion is supported by multiple independent datasets and bibliometric studies.

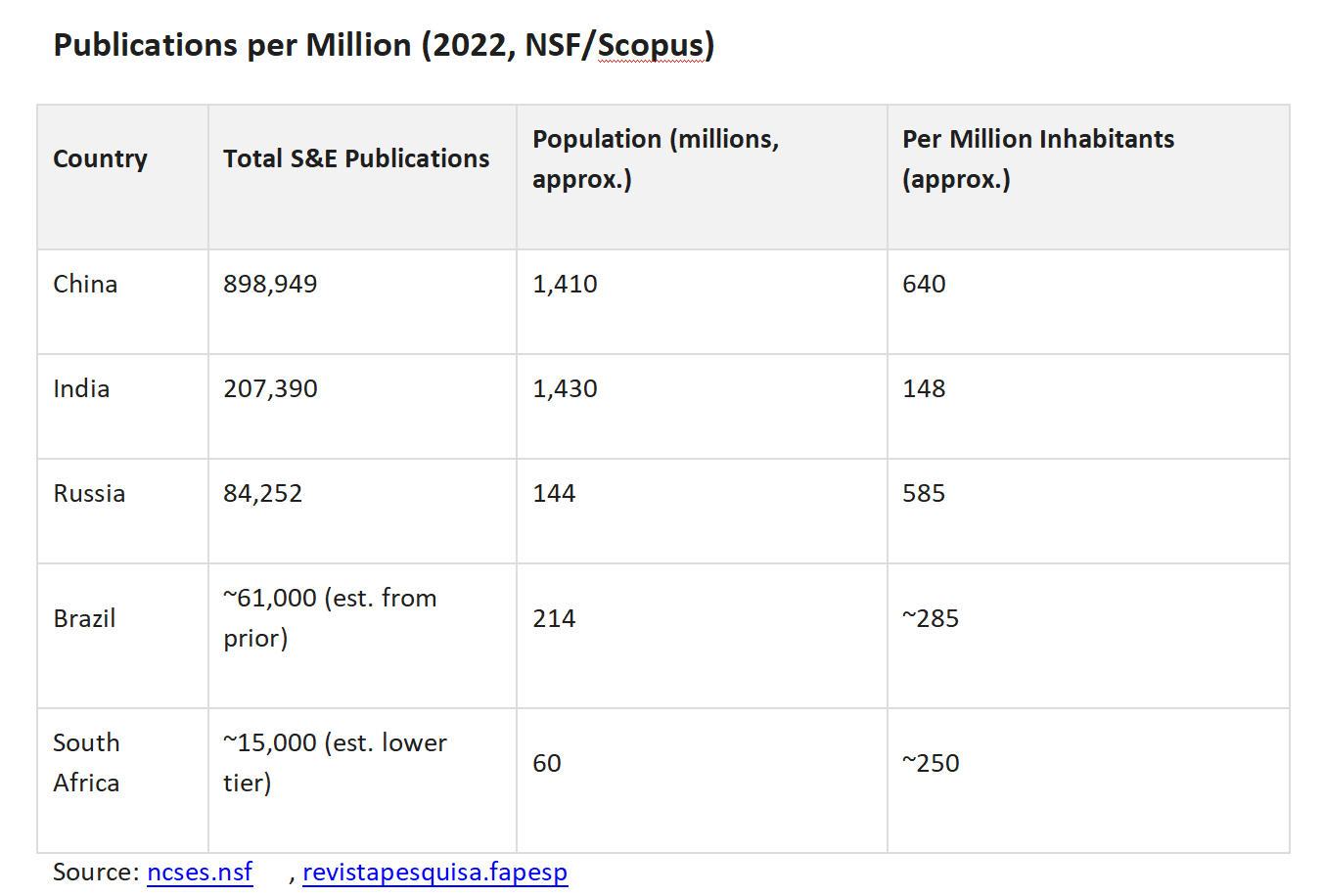

A bibliometric analysis of BRICS nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—reveals that China leads in publication numbers, producing significantly more than the combined outputs of the other BRICS countries. Throughout much of the study period, these nations have similar income levels. The study indicates that with approximately 1.67 million researchers, China generated around 2.8 million publications from 2013 to 2017, resulting in a much higher publication count per researcher compared to Brazil, India, Russia, and South Africa, all of which exhibit lower total outputs relative to their researcher populations.

China also leads BRICS nations in both scientific publications and patent applications per million inhabitants based on the most recent available data, which covers 2023 for patents (WIPO 2025 report) and remains 2022 for publications (NSF 2023 report, with no newer comparable BRICS-wide figures found).

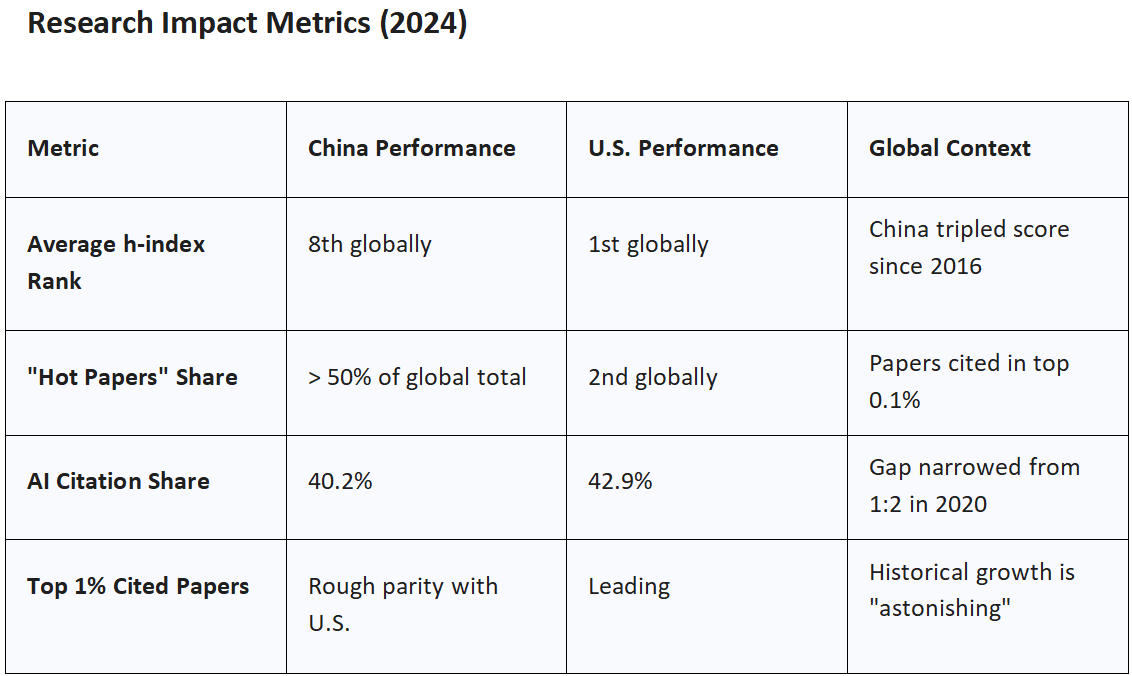

The prestigious Nature Index tells a similar story. China's Share in elite natural science journals per 10 million people (227.87) is nearly 28 times higher than that of Mexico (7.99), despite having a slightly lower per capita GDP. Furthermore, China’s h-index—a measure of both productivity and citation impact—has nearly tripled since 2016, making it the only non-high-income economy to reach the global top 10 for research quality.

Further analyses by the World Bank and G20 illustrate that while India and Brazil show strong growth in publication numbers, they still trail far behind China in total volume, despite all three being large middle-income economies with comparable GDP per capita levels. An Elsevier report on research trends within the G20 highlights that China's publication growth rate of about 9.3% annually from 2012 to 2022 is on par with India's, yet it is built on a much more substantial base, indicating that, at similar income levels, China maintains significantly higher publication intensity relative to its population than most of its G20 middle-income counterparts.

When examining large middle-income countries in the Global South—including China, India, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Indonesia, and Türkiye—China consistently ranks near the top globally in terms of total publications and its share of global output in key research fields like artificial intelligence and sustainable development goals (SDG)-related studies. For instance, in AI research, China is recognized as the leading global contributor, whereas countries such as India, Brazil, Iran, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Türkiye rank lower on the list, suggesting that their publication counts are substantially inferior despite having similar or lower GDP per capita.

Impact-weighted indicators, such as the national h-index and field-weighted citation impact, position China as the leading middle-income nation, surpassing India, Brazil, South Africa, and Türkiye in both the quantity and citation impact of research outputs at comparable income levels. Comparative studies of economic development and scientific output within BRICS further emphasize that, when GDP and population are controlled, China emerges as an outlier with a markedly higher rate of scientific knowledge production than its BRICS peers.

China’s outstanding performance in innovation is also reflected in the number of patents filed per million inhabitants. WIPO's 2024 report analyzes the resident-plus-abroad filings from 2023, revealing that China is the clear leader in this area, with submissions significantly surpassing those of other nations, even when adjusted for population size. To calculate per capita filings, the number of applications is divided by the approximate 2023 populations, which are as follows: China with 1.41 billion, India with 1.43 billion, Russia with 144 million, Brazil with 216 million, and South Africa with 60 million.

Specifically, China received around 1.64 million applications, translating to approximately 1,164 applications per million people. In contrast, India filed between 50,000 and 70,000 applications—signifying rapid growth despite a low absolute number—resulting in about 40 to 50 applications per million. Russia submitted around 10,000 applications, equating to about 70 per million. Brazil's filings ranged between 5,000 and 10,000, yielding approximately 25 to 45 per million, while South Africa recorded fewer than 5,000 applications, giving it a rate of under 80 per million.

Notably, China's per capita application rate is 20 to 30 times higher than that of its peers. Preliminary data for 2024 indicates continued growth, with China's total expected to reach about 3.2 million applications, or around 1,700 per million, while Brazil has seen a 27% increase, although its absolute numbers remain low.

Structural Drivers: The New Whole-of-Nation System

The primary mechanism behind China’s outlier status in scientific output is the revitalized “new system for mobilizing resources nationwide” (新型举国体制 , or NSMRN). This governance model allows the state to mobilize national resources with a degree of central coordination that is functionally absent in market-driven economies. The NSWN differs from its Mao-era predecessor by enlisting the private sector and leveraging market mechanisms, yet it maintains the core objective of " concentrate efforts on key undertakings" (集中力量办大事).

This system is overseen by the Central Science and Technology Commission (CSTC), established in March 2023, which effectively centralizes the leadership of Science, Technology, and Innovation (STI) under the direct supervision of CCP. The NSMRN is specifically designed to tackle "techno-industrial bottlenecks"—areas where China remains dependent on foreign technologies, such as advanced semiconductors, aircraft engines, and high-specification machining. By coordinating consortia across the entire innovation chain—from fundamental research in labs to commercial application in the military and industrial sectors—the state ensures that scientific activity is aligned with national strategic priorities.

The Applied Research bias and the Leapfrog Strategy

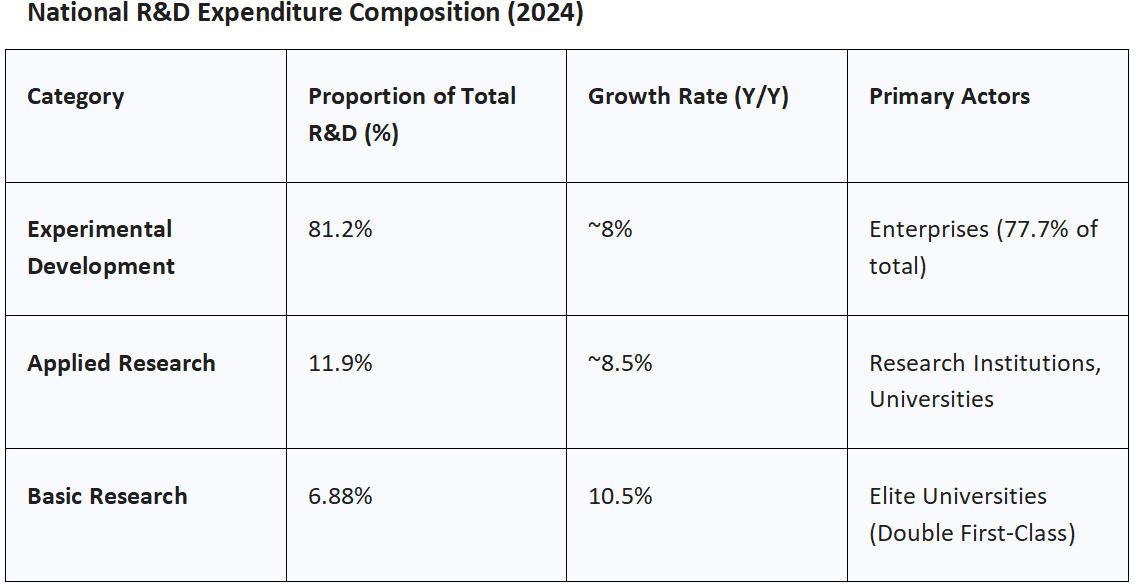

A granular analysis of China's R&D expenditure reveals a strategic preference for applied outcomes over basic research. In 2024, China’s total R&D spending reached 3.61 trillion yuan ($496.32 billion), an 8.3% increase over 2023. This expenditure represents 2.68% of China's GDP, which is rapidly approaching the OECD average of 2.73%. However, the internal allocation of these funds is highly skewed toward experimental development.

This focus on the "D" in R&D allows China to maximize its immediate scientific-to-industrial conversion rate. While the U.S. and South Korea allocate significantly higher proportions of their GDP to basic research, China’s model prioritizes sectors like New Energy Vehicles (NEVs), where output reached 13.168 million units in 2024, up 38.7%. This "Leapfrog Strategy" utilizes scientific research to dominate emerging industries before established players can entrench themselves. The result is a scientific landscape where China holds a dominant lead in 57 out of 64 critical technology categories identified by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), particularly in energy, environment, and advanced manufacturing.

Human Capital: The Scale and Depth of the Scientific Labor Force

China’s scientific output is fundamentally underpinned by its massive expansion of higher education, a process that began in earnest in 1999. The sheer volume of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) talent produced annually is arguably the most significant factor in its outlier status. In 2022, China awarded more than 50,000 STEM doctorates, compared to roughly 34,000 in the United States. By 2025, China has awarded twice the number of STEM PhDs compared to the US.

This expansion is characterized by a high degree of specialization. Approximately 44% of Chinese students major in Science and Engineering, whereas the figure is only 16% in the United States. This creates a dense scientific labor force that, while still smaller than the US as a percentage of the total population (0.4% in China vs. 3.1% in the U.S. as of earlier 2010s data), is larger in absolute terms for engineers and rapidly catching up in basic scientists.

This "STEM explosion" is complemented by the "Returnee" phenomenon. Historically, China’s brightest minds were trained abroad; however, a combination of state-funded recruitment programs (like the Thousand Talents Plan) and increasing research budgets within China has encouraged a massive influx of high-level talent back into Chinese institutions. These returnees bring established international networks and advanced methodologies, contributing to the rapid qualitative shift in Chinese research. By 2024, Chinese scientists were leading nearly half of all collaborations with American counterparts, up from 30% in 2010.

Institutional Excellence: The Double First-Class Initiative

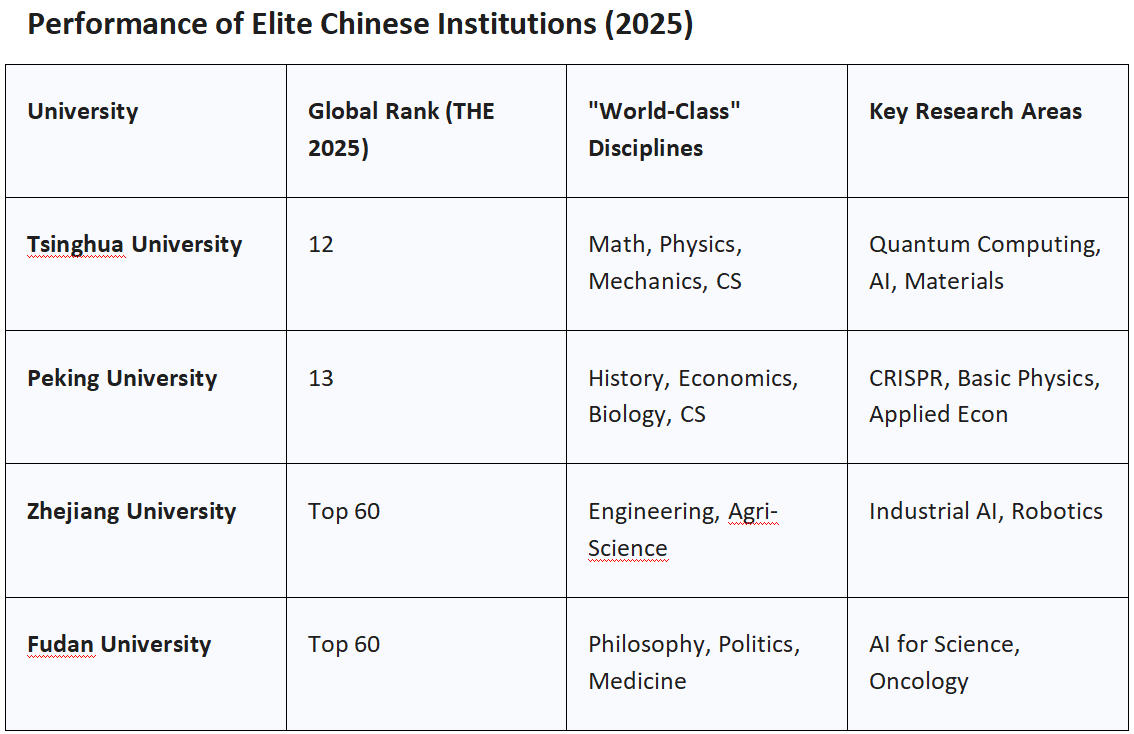

The "Double First-Class" (双一流) initiative represents a landmark reform in China’s higher education system, designed to concentrate resources into elite universities and disciplines to compete at the global frontier. By 2025, the results of this sustained commitment were evident in global university rankings. For the first time, China listed 346 institutions in the Global 2000, surpassing the United States’ 319.

The initiative provides significant funding for research infrastructure and faculty development at universities like Tsinghua and Peking University, which now rank 12th and 13th globally in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Crucially, 9 of the world’s top 10 research institutions in 2025 are Chinese, with Harvard being the sole Western holdout in the elite tier.

The efficacy of these institutions is reflected in their "research efficiency." Studies show that 69.2% of "Double First-Class" universities have higher research efficiency than teaching efficiency, highlighting a policy-driven mandate to prioritize high-impact publications and patents. This institutional focus has led to a situation where Chinese scholars now account for 35.2% of all papers published in high-impact journals globally.

Resolving the Quantity vs. Quality Debate: The 2020 Pivot

For decades, Western analysts dismissed China’s rising publication volume as a product of "paper mills," plagiarism, and a "publish or perish" culture fueled by cash bonuses for SCI-indexed papers. However, the data from 2024 confirms that China has effectively transitioned from volume to quality.

In February 2020, the Ministry of Science and Technology (MoST) and the Ministry of Education (MoE) issued two transformative guidelines aimed at reforming research evaluation. These policies sought to eliminate "SCI-worship" and overemphasis on papers-publishing. Key reforms included:

● Representative Works System: Researchers are evaluated on a maximum of five "most important" papers rather than a long list of minor works.

● Domestic Journal Quota: At least one-third of a researcher's representative works must be published in domestic Chinese journals with international influence.

● Ban on Publication Bonuses: Direct monetary rewards for publishing in SCI journals were prohibited, removing the financial incentive for academic misconduct.

The impact of this pivot has been a "rout" of international competition in high-quality venues. China’s Nature Index output grew by 95% from 2020 to 2024, while the U.S. grew by only 9.5%. Furthermore, the average citation rate for Chinese papers—17.24 per paper—has exceeded the global average for two consecutive years as of 2024.

This transition to high-impact science indicates that China’s scientific apparatus has matured. The success in elite journals like Nature, Science, and Cell demonstrates that Chinese researchers are now shaping entire fields rather than merely contributing to the periphery of existing research.

Technological Dominance and the "Hilly Landscape"

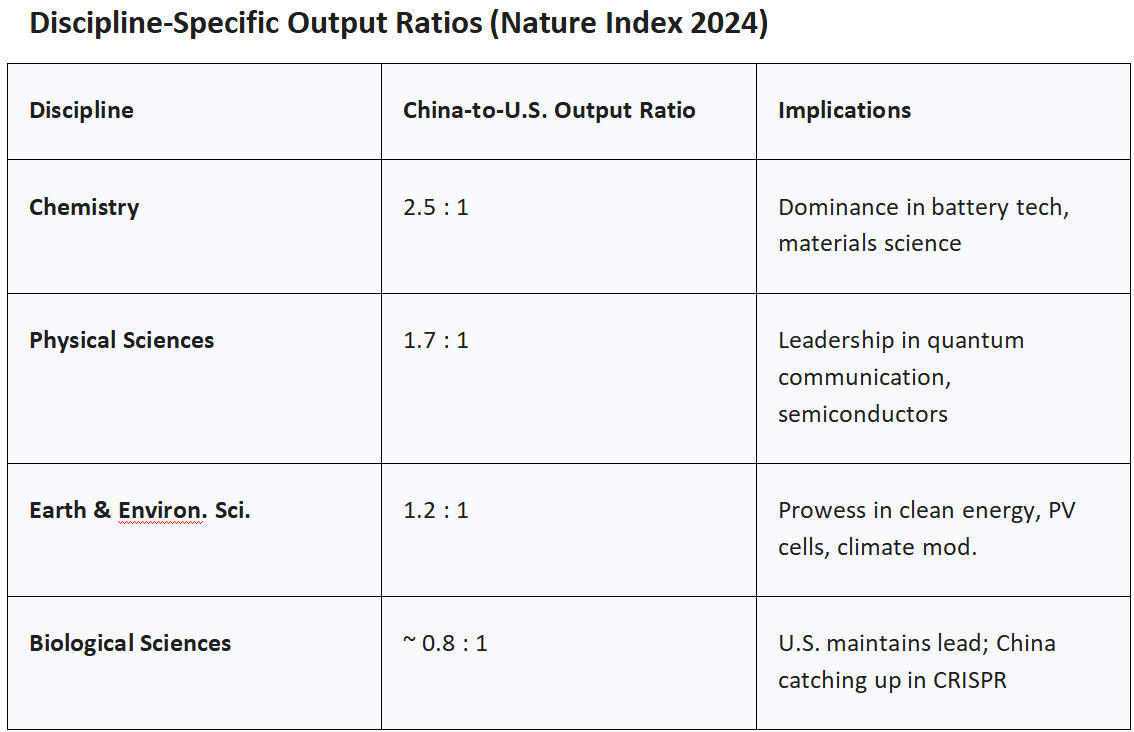

China’s scientific output is not uniform across all disciplines; it is a "hilly landscape" defined by strategic specialization. In the physical sciences, chemistry, and earth and environmental sciences, China has moved decisively ahead of the United States.

In the Energy and Environment domain, China accounts for 46% of top-tier publications, compared to just 10% for the United States. This concentration of intellectual capital directly correlates with China's industrial leadership in the green transition. For example, China’s output of solar cells reached 0.68 billion kilowatts in 2024, a 15.7% increase, fueled by scientific breakthroughs in photovoltaic efficiency.

AI and Robotics: The Frontier of Strategic Competition

Artificial Intelligence represents the most intense arena of competition. China has published 273,900 AI papers in 2024, more than four-and-a-half times its 2015 total. By 2022, China’s AI research output had already outstripped the combined output of the EU and the United States. While the U.S. still holds an advantage in "foundational" AI research, China leads in "AI for Science" (AI4S) and AI applications, accounting for 41.6% of all AI-related citations in government policies and clinical trials.

In robotics, China holds a significant lead in publications and is rapidly commercializing this research. Service robot production reached 10.519 million in 2024, up 15.6%, while industrial robot output grew by 29.8% in the first three quarters of the year. This synergy between scientific output and industrial production is a hallmark of the Chinese model, ensuring that research does not remain confined to academia but drives tangible economic and military outcomes.

Geopolitical Catalysts: Decoupling and the Drive for Autonomy

The acceleration of China’s scientific output has been catalyzed, rather than hindered, by increasing geopolitical friction. U.S. export controls and technology sanctions have reshaped Chinese industrial and science policy toward "self-reliance". President Xi Jinping’s emphasis on creating an "autonomously controllable" hardware and software ecosystem has turned scientific research into a matter of national security.

For example, in response to semiconductor sanctions, China has pooled resources into the "National Integrated Computing Network" to optimize existing computing power across public and private data centers. The "Eastern Data, Western Computing" project, launched in 2022, is a direct application of the Whole-of-Nation system to overcome technological bottlenecks.

This drive for autonomy is reflected in the patenting data. By the end of 2024, China had 14 high-value invention patents per 10,000 people. Invention patent grants increased by 13.5% year-on-year, a clear signal that the country is successfully translating its elite research into legally protected intellectual property that can be used to secure global market share and circumvent foreign dependencies.

Conclusion: Why China is a Systematic Scientific Outlier

The fact that China is a scientific outlier both in terms of per capita output and total output rests on its ability to produce high-income scientific results on an upper-middle-income budget. While peers at its income level are still building basic research infrastructure, China has punched above its weight from its per capita wealth. This has been achieved through:

1. Saturation of STEM Labor: producing double the number of STEM PhDs as the U.S. by 2025 to drive both volume and impact.

2. Whole-of-Nation Resource Mobilization: utilizing centralized commissions to direct research toward techno-industrial bottlenecks.

3. Elite Institutional Focus: elevating 42 universities into the global top 100 through the Double First-Class initiative.

4. Strategic Quality Pivot: reforming incentive systems in 2020 to prioritize high-impact journals and "hot papers" over bulk publication.

5. Cluster-Driven Innovation: leveraging 24 world-class S&T clusters to bridge the gap between lab research and industrial application.

China’s research ascendancy is not a temporary deviation but a new model of developmental science. As the country nears the high-income threshold, it does so with a scientific infrastructure that already rivals or exceeds the most advanced economies in the world.

References

- Statistical communiqué of the people's republic of China on the 2024 national economic and social development, https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202502/t20250228_1958822.html

- GDP per Capita (2025) - Worldometer, https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-per-capita/

- China's Historic Rise to the Top of the Scientific Ladder - Quincy Institute, https://quincyinst.org/research/chinas-historic-rise-to-the-top-of-the-scientific-ladder/