Identity politics, while aiming to champion marginalized groups, carries several detrimental consequences that impede social unity and individual empowerment. A major criticism is its contribution to social fragmentation.

By highlighting group differences based on race, gender, or sexual orientation, it can create divisions instead of fostering unity, hindering the formation of broad-based coalitions and potentially increasing tensions and backlash from those feeling excluded. Furthermore, identity politics often simplifies individuals to a single identity aspect, neglecting the complexity of human experience. This reductionist approach reinforces stereotypes and essentialist views, prioritizing group affiliation over individual uniqueness and potentially silencing dissenting voices within groups.

Concerns also exist regarding the cultivation of a victimhood mentality, emphasizing grievances over empowerment and potentially undermining individual agency and resilience, especially in already vulnerable educational settings. Tokenism is another potential pitfall, where symbolic representation overshadows meaningful change, allowing political elites to exploit identity issues without genuine commitment to addressing underlying problems.

In addition, critics argue that identity politics distracts from broader socio-economic issues like class struggle, potentially hindering collective action against systemic inequalities affecting all marginalized groups. In conclusion, despite its role in advocating for marginalized voices, identity politics' negative impacts—social fragmentation, reductionism, victimhood mentality, tokenism, and distraction from broader issues—significantly challenge the pursuit of genuine social cohesion and justice.

The PRC before 1978 witnessed a turbulent period profoundly shaped by class-based identity politics, a defining feature of Mao’s rule. This wasn't simply a matter of socioeconomic stratification; it was a highly politicized system that dictated social standing, opportunities, and even survival. Maoist ideology, rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles, rigidly categorized the population into distinct classes, each with inherent political significance and often antagonistic relationships.

The core of this system was the class struggle. Land ownership played a crucial role. Landlords, who owned land but didn't work it, were positioned as the ultimate exploiters. Wealthy peasants, who owned or rented land and employed hired labor, were also seen as part of the exploiting class, albeit to a lesser extent. Below them were various strata of the "middle" and "petty" bourgeoisie, encompassing small business owners, professionals, self-employed individuals, and teachers. The semi-proletariat comprised poor peasants and workers with insufficient assets, while the proletariat consisted of factory workers and miners entirely dependent on wages.

This already complex categorization was further complicated by the inclusion of explicitly political groups. "Counter-revolutionaries," encompassing historical reactionaries and remnants of the Kuomintang (the Nationalist Party), were marked as enemies of the state. Similarly, "bad elements"—individuals deemed disruptive or problematic during periods of social upheaval—faced severe consequences. The 1957 Anti-Rightist Campaign dramatically expanded this system, labeling intellectuals and democrats who criticized the Communist Party leadership as "rightists," subjecting them to persecution and social ostracism.

This intricate system of class classification wasn't merely theoretical; it had profound real-world effects. It shaped social relationships, determined access to education and employment, and influenced the distribution of resources. Families were affected, with the class status of one member impacting the entire family's standing. Social networks were fractured, as individuals navigated the complexities of class affiliation and the ever-present threat of denunciation.

The significance of this class-based identity politics diminished significantly after 1978, with the implementation of Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms and the "opening up" of China. The emphasis on class struggle gradually faded, replaced by a focus on economic growth and modernization. While socioeconomic disparities persist in contemporary China, the rigid, politically charged class system of the Mao era is largely a thing of the past. However, the legacy of this period continues to shape Chinese society and politics, influencing perceptions of social hierarchy and power dynamics.

Modern China's approach to governance rests on a fundamental principle: "harmony in diversity" (和而不同, hé ér bù tóng). This philosophy, evident from the nation's founding, acknowledges and celebrates diversity. The autonomy granted to ethnic minorities and the "one country, two systems" framework applied to Hong Kong exemplify this approach. A potential future reunification with Taiwan could further showcase this unique model of coexisting systems within a single nation—a model unseen elsewhere in the world.

This principle also shapes China's attitude towards identity politics. Rather than emphasizing a singular, dominant identity, the focus is on managing and integrating diverse identities within a unified framework. The emphasis is on shared national identity while respecting and accommodating regional, ethnic, and other forms of identity. This approach aims to avoid the potential divisiveness of identity-based conflict, prioritizing social harmony and stability.

Having learned from its recent history, the CCP and Chinese society are committed to avoiding past mistakes. Instead of employing Marxist class divisions, the CCP aims to foster a harmonious society by emphasizing commonalities among diverse groups. Current official policies strive to balance individual freedom with social responsibility, drawing on China's collectivist traditions. A healthy dose of collectivism, it is hoped, could potentially mitigate the negative impacts of Western-style identity politics.

The rise of identity politics in the West is intricately linked to the increasing emphasis on individualism and personal rights in modern society. While celebrating individual autonomy offers undeniable benefits, its unchecked growth has inadvertently fostered a climate conducive to identity-based movements, often with divisive consequences. Individualism, championing self-expression and autonomy, empowers individuals to define their identities and pursue goals without undue societal pressure; however, this focus can overshadow collective responsibility and interconnectedness.

Contemporary society's prioritization of personal rights often neglects this interdependence, leading to decreased community engagement and a diminished sense of shared responsibility for broader social issues. This creates conditions for societal fragmentation, where individuals retreat into identity groups rather than building bridges across communities. Identity politics emerges as a response to systemic injustices faced by marginalized groups, articulating struggles through shared experiences of oppression. While aiming for empowerment, it can paradoxically exacerbate divisions by highlighting differences. The interplay between individualism and identity politics creates a cycle: the assertion of personal rights without corresponding collective responsibility.

This manifests in increased polarization, erosion of community, and superficial representation, replacing genuine inclusion and meaningful change. Mitigating these negative consequences requires balancing individual rights and collective responsibilities—cultivating a "connected individualism" that value both personal autonomy and social cohesion, fostering intergroup dialogue to bridge divides, and prioritizing collective action to address social injustices as shared challenges. Ultimately, a more just and cohesive society necessitates a conscious effort to balance the celebration of individual identities with a strong sense of collective responsibility.

Collectivism, on the other hand, prioritizing group well-being over individual interests, offers potential solutions to the challenges posed by identity politics. By fostering shared responsibility and community, it can address social fragmentation, reductionism, and the neglect of collective responsibilities often arising from identity-based politics.

Collectivism promotes unity by encouraging individuals to recognize their interconnectedness, fostering a shared purpose that bridges divisions between identity groups and leading to collaborative efforts to address common challenges, thus reducing the emphasis on divisive identity markers. It encourages inclusivity by valuing diversity within a framework of shared goals, acknowledging individual differences without reducing people to their identities. Focusing on collective well-being creates an environment where all voices are valued, counteracting exclusionary tendencies.

Collectivism fosters dialogue and understanding by encouraging open communication among diverse groups, prioritizing communication over conflict to address grievances while acknowledging the complexity of individual experiences. This dismantles stereotypes and fosters empathy, reducing tensions from identity-based conflicts. It balances rights with responsibilities by emphasizing social responsibility alongside individual rights, framing rights within community obligations to encourage individuals to consider the impact of their actions on others. This creates a more equitable society where collective needs are prioritized alongside personal freedoms, addressing the neglect of broader social responsibilities often seen in identity politics.

Additionally, collectivism challenges essentialist notions by promoting a dynamic understanding of identity, acknowledging change and complexity. Instead of viewing identities as fixed categories, it recognizes the fluidity of identities and multiple affiliations, avoiding the reductionism often accompanying identity politics. Collectivism offers valuable strategies for mitigating the negative impacts of identity politics by promoting unity, inclusivity, dialogue, and a balance between rights and responsibilities.

By fostering a community-oriented approach that values both individual experiences and collective goals, societies can address systemic inequalities without succumbing to the divisiveness and reductionism inherent in narrow identity politics, enhancing social cohesion and empowering individuals to contribute meaningfully to collective progress.

In a nation as vast and diverse as China, the tapestry of ethnic groups woven into its social fabric is both rich and varied. From the lush landscapes of Inner Mongolia to the vibrant traditions of Tibet, each region tells a unique story of heritage and identity.

The journey towards national unity and cultural preservation in China has been one of deliberate steps and inclusive policies. Through legal frameworks like the Constitution and the Law on Regional National Autonomy, the principles of ethnic solidarity have been enshrined, ensuring a foundation of unity across diverse communities.

Efforts to bridge historical divides and eliminate discriminatory practices have been pivotal in fostering a sense of inclusivity and harmony. Historical directives, such as the 1951 proclamation addressing derogatory references to minority groups, stand as testaments to a nation striving for unity.

In the realm of education and language, China has embraced a policy of safeguarding and developing ethnic languages and scripts. By respecting the linguistic diversity of its 56 ethnic groups and promoting bilingual education, the nation stands as a testament to the celebration of cultural heritage.

Cultural practices and religious beliefs have been honored and protected, recognizing the importance of traditions in shaping identity. From the Islamic communities of the Hui and Uygur to the Buddhist traditions of the Tibetan and Dai peoples, China's commitment to respecting customs and beliefs is a cornerstone of national unity.

China's approach to ethnic relations is fundamentally one of promoting equality and unity within a unified, multi-ethnic state. This policy centers on regional ethnic autonomy, empowering minority groups while maintaining national cohesion. This model of "precision autonomy," fostering group identity and well-being, stands in stark contrast to genocide, a crime defined by the specific intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

Instead of aiming for destruction, China's policy actively promotes the flourishing of each ethnic group. The dramatic growth of the Uyghur population in Xinjiang—from 2.2 million to 12 million over the past 60 years—along with a corresponding increase in life expectancy from 30 to 74.7 years, serves as compelling evidence of this. The widespread popularity of Uyghur actors and actresses across China and internationally further underscores the success of this policy in promoting cultural visibility and integration.

This demonstrable success in fostering both ethnic identity and national unity refutes accusations of genocidal intent. China's policy is, in fact, the antithesis of group destruction; it is a policy of group preservation and empowerment within a shared national framework.

As China continues its journey towards inclusivity and cultural vibrancy, the nation remains dedicated to fostering a climate where diversity is celebrated and every voice is heard. Through a tapestry of languages, traditions, and beliefs, China's mosaic of ethnic groups continues to weave a narrative of unity in diversity, embodying a nation that cherishes its cultural tapestry.

China's ethnic policy is built upon the principles of ethnic equality, ethnic unity, and common prosperity for all ethnic groups. The state safeguards the equal rights of ethnic minorities and the Han majority in political, economic, and cultural spheres through a series of laws and regulations, prohibiting any form of ethnic discrimination or oppression. To foster ethnic unity, the government encourages exchange and cooperation among different ethnic groups and enhances the cohesion of the Chinese nation through various cultural activities. Furthermore, to achieve common prosperity, the state has introduced a range of preferential policies to support the economic development and social progress of ethnic minority regions.

Specifically, preferential policies for ethnic minorities include, but are not limited to, the following aspects:

Education Benefits: For example, bonus points on the college entrance examination (Gaokao) to help ethnic minority students gain more opportunities in higher education admission.

Employment Support: For instance, giving priority to ethnic minority individuals in civil service recruitment under equal conditions; and offering preferential policies to ethnic minority fresh graduates from regular universities who apply to institutions in "Tier 2 or 3" enrollment zones and commit to working in ethnic autonomous areas designated by the State Council.

Economic Development Support: Increasing investment in infrastructure construction in ethnic minority regions to boost local economic development and improve livelihoods.

Cultural Protection: Respecting and protecting ethnic minority languages, scripts, customs, and religious beliefs, and supporting the inheritance and development of ethnic minority cultures.

Regarding the situation of the Uyghur ethnic group, the Chinese government has implemented a series of measures to promote harmony, stability, and development in the Xinjiang region. These measures include strengthening the work of vocational skills education and training centers, which aim to provide training in areas such as language, legal knowledge, and vocational skills. This is intended to help individuals influenced by extremist ideologies reintegrate into society. This approach is considered to help reduce the threat of terrorism, improve the quality of life for local residents, and promote harmonious regional development.

It's important to note that there are different views and interpretations internationally regarding re-education policies. The Chinese government emphasizes that its purpose is counter-terrorism and de-radicalization, and it is continuously adjusting and refining relevant policies to ensure they align with human rights protection standards. Simultaneously, Chinese officials state that vocational skills education and training centers strictly adhere to the Chinese Constitution and laws, fully safeguarding the basic rights of trainees and helping them secure better employment opportunities and improve their living standards.

In summary, China's ethnic policy and its implementation aim to safeguard the legitimate rights and interests of all ethnic groups, promote harmonious coexistence among them, and foster common prosperity and development nationwide.

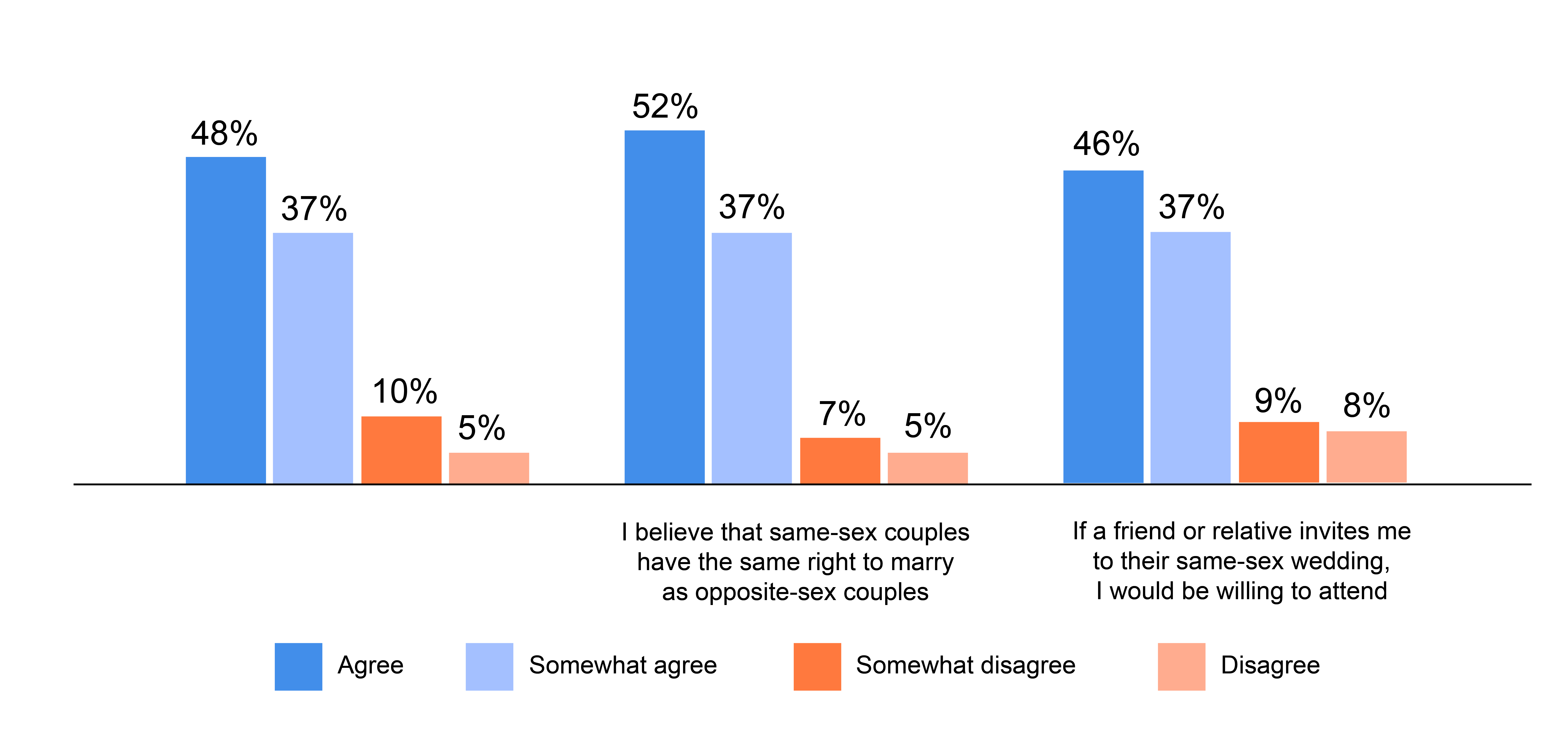

In 2024, researchers from the Williams Institute of UCLA conducted a survey on attitudes toward LGBTQ people in mainland China. The result shows a predominantly positive outlook among respondents.

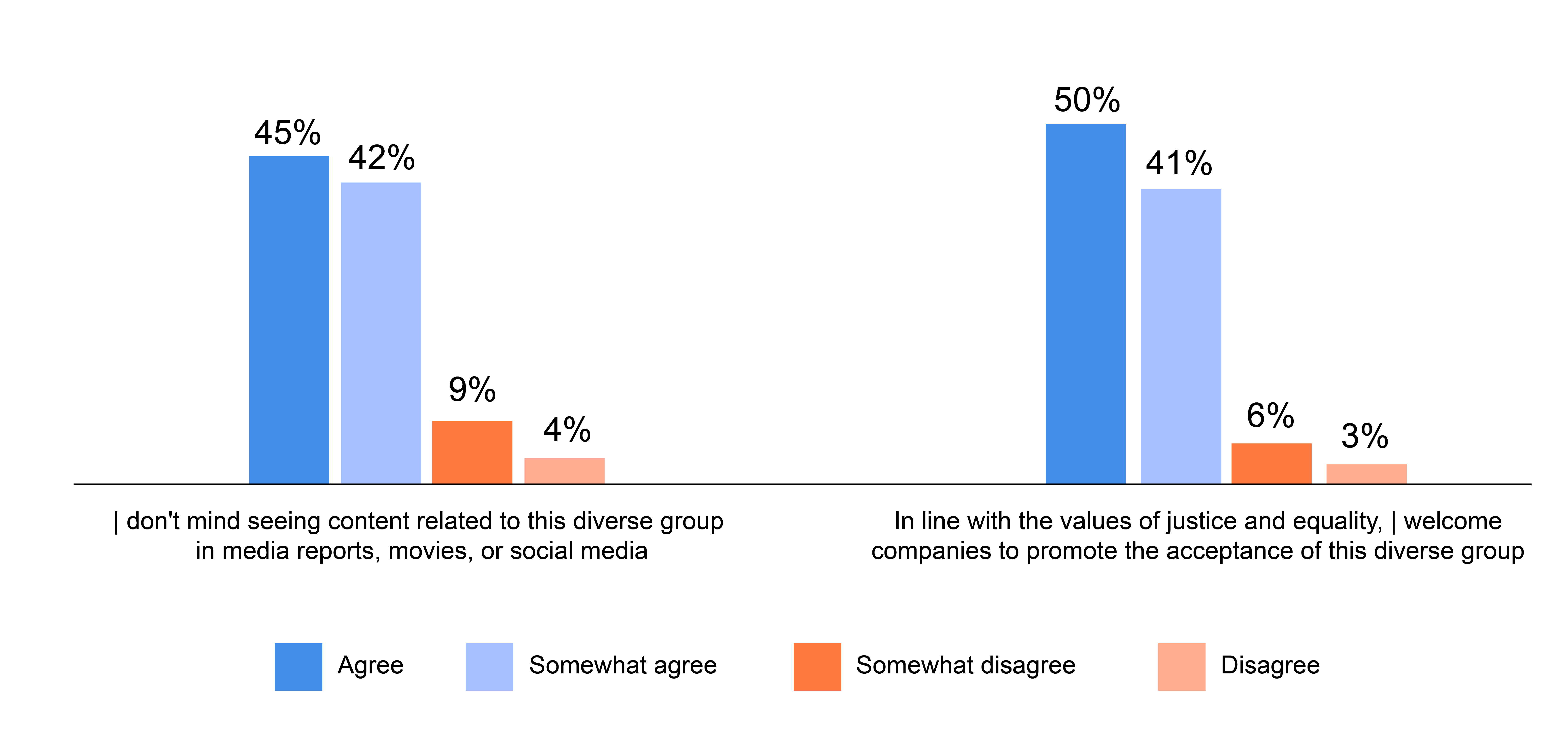

Administered to a nationally representative sample of 2,926 mainland Chinese adults, the survey assessed familiarity with LGBTQ people and attitudes towards various policy issues, including workplace discrimination, same-sex marriage, same-sex parenting, media portrayals, and corporate support for LGBTQ inclusion.

A significant majority expressed support for fair treatment in the workplace (62%) and protection from violence in schools (68%), demonstrating considerable agreement on crucial issues of equality and safety. While slightly lower, support for same-sex marriage (52%) and same-sex parenting (48%) was also notable. Personal acceptance, such as having an LGBTQ neighbor or attending a same-sex wedding, received somewhat less support (around 46%).

Attitudes toward LGBTQ families. Source: Meyer, I.H et al.

These positive attitudes were significantly correlated with several demographic factors: younger age, female gender, higher income, higher education, residence in a major city, and, most significantly, personal familiarity with LGBTQ individuals. The study's findings contrast with some previous research indicating more negative views, likely due to sampling biases in those earlier studies. The current study's larger, more representative sample suggests a considerable portion of the Chinese public supports greater LGBTQ rights and protections. The strong support for workplace fairness and school protections, in particular, indicates areas where policy changes could effectively reflect public sentiment.

Promotion of LGBTQ people in the workplace and the media. Source: Meyer, I.H et al.

In contrast, Chinese government’s stance on LGBTQ issues can be summarized as "non-discrimination, non-encouragement, non-suppression." At the policy level, it neither openly advocates for nor opposes LGBTQ rights, aiming to avoid negatively impacting the LGBTQ community. This approach reflects a respect for individual choices while also considering social stability and cultural differences.

Historically, Chinese law and social attitudes towards LGBTQ individuals have been varied. For instance, some ancient literary works depict homosexuality, suggesting a degree of social tolerance. However, in modern society, traditional values have led to limitations on the living space and freedom of expression for the LGBTQ community in China.

During the 2018 Universal Periodic Review of the UN Human Rights Council, China's representative outlined its basic position on LGBTQ people, including respecting their right to health and equal social security, while simultaneously not granting LGBTQ individuals the right to same-sex marriage. These policies are determined by China's historical and cultural values.

To avoid being hijacked by western-style identity politics and distracted from addressing challenges facing the majority of the population, the Chinese government's approach to LGBTQ issues is conservative and cautious, prioritizing social harmony and stability while gradually considering and exploring how to provide necessary support and protection while respecting individual choices.

China's constitution offers a framework for anti-discrimination, yet LGBTQ+ individuals lack robust legal protection, and same-sex marriage remains illegal. This absence isn't simply a matter of legal oversight; it reflects a complex interplay of social, cultural, and political considerations.

Legalizing same-sex marriage would undoubtedly raise significant questions. How would same-sex couples address procreation? Would surrogacy or relaxed adoption policies be considered, and what impact would these have on women and children? These are not merely LGBTQ+ concerns; they touch the very fabric of Chinese society.

In fact, many Chinese—including some within the LGBTQ+ community—oppose immediate legalization of same-sex marriage. While acknowledging the importance of marriage equality, they prioritize social harmony and stability. During an interview conducted by Chinese researchers, one interviewee from LGBTQ+ community stated, "Our love doesn't need legal validation. Social stability is more important." This sentiment highlights a deep-seated concern about potential societal disruption and a typical collectivist mindset in stark contrast with the individualism of their western counterparts.

Legalizing same-sex marriage isn't simply a legal change; it's a profound societal shift impacting deeply held cultural traditions and family structures. Any reform must carefully consider the potential consequences to ensure a smooth transition and avoid exacerbating social tensions.

This doesn't mean ignoring LGBTQ+ rights. Instead, China should explore alternative paths to ensure their well-being, such as strengthening anti-discrimination laws and promoting greater social understanding through education and public awareness campaigns. The goal is to create a more inclusive society that respects individual rights while maintaining social cohesion. The path forward requires a nuanced approach that balances individual freedoms with the preservation of social harmony.

The preceding analysis of identity politics reveals a complex interplay between individual rights and collective responsibility, particularly when viewed through the lens of China's historical and contemporary experiences. While the West grapples with the divisive potential of identity-based movements rooted in individualism, China's approach, shaped by its history with class-based identity politics and its current emphasis on "harmony in diversity," offers a contrasting perspective.

China's commitment to social harmony and stability, while sometimes criticized for its limitations on individual freedoms, provides a framework for managing diverse identities within a unified national identity. The success of this approach, however, remains contingent on its ability to balance the preservation of social cohesion with the genuine protection of the rights and well-being of all its citizens, including LGBTQ+ individuals and ethnic minorities. The ultimate question remains whether a collectivist approach can effectively address systemic inequalities and foster genuine inclusivity without sacrificing individual freedoms, or if a different balance between individual rights and collective responsibility is needed to achieve a truly just and harmonious society. Further research and open dialogue are crucial to understanding the complexities and potential pitfalls of both Western-style identity politics and China's alternative model.