For four decades, China, led by CCP, has defied expectations, orchestrating an economic transformation of unprecedented scale and speed. Its achievements merit serious consideration for a Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, not just for the sheer magnitude of its growth, but for the innovative policies and strategic execution that underpinned it. This isn't merely about impressive numbers; it's about a paradigm shift in how a nation can lift itself from poverty and achieve global economic prominence.

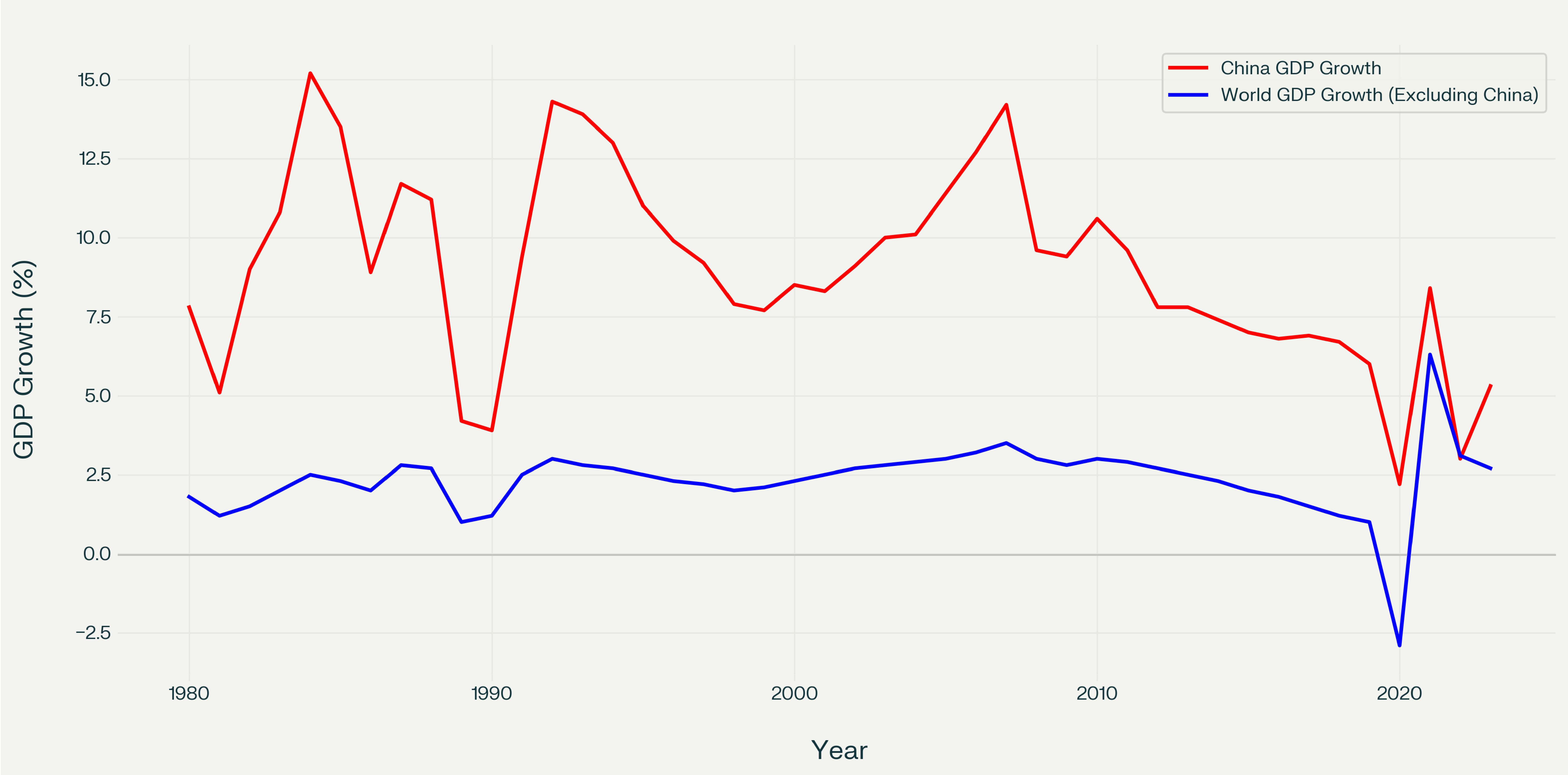

Unprecedented Growth: The headline figure is undeniable: an average annual GDP growth rate of approximately 8.8% from 1984 to 2024. This sustained expansion, punctuated by periods of even more dramatic growth (reaching 15.2% in 1984 and a remarkable 18.7% in Q1 2021), propelled China from a relatively small economy to the world's second largest. This wasn't a fleeting boom; it represents decades of consistent progress, demonstrating sustainable economic growth and resilience in the face of global economic fluctuations.

China's GDP Growth vs World GDP Growth (Excluding China) Since 1980, data source: World Bank

Poverty Eradication on a Grand Scale: While GDP growth is impressive, its impact on the lives of ordinary Chinese citizens is even more profound. The reduction in poverty is remarkable. Since the late 1970s, over 800 million people have been lifted out of poverty – an achievement unparalleled in human history. This achievement transcends economic statistics; it represents a fundamental improvement in the well-being and life expectancy of a vast segment of the global population. By comparison, according to various estimates, about 200 million people have been lifted out of extreme poverty outside of China in the same period.

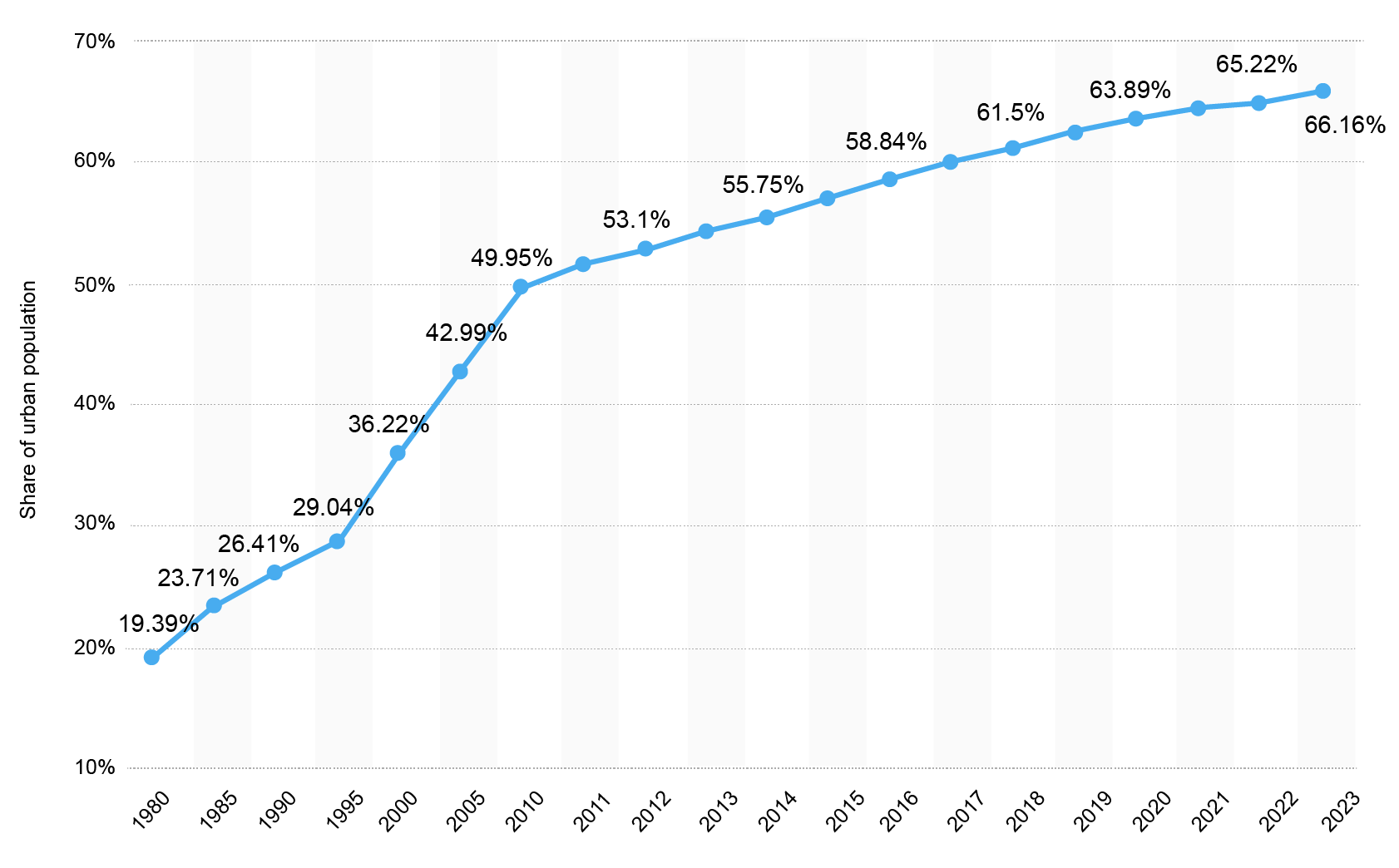

Strategic Urbanization and Employment: China's remarkable urbanization story is intrinsically linked to its economic success. As of the end of 2023, China's urbanization rate among permanent residents reached 66.16%, with the urban population increasing from 170 million in 1978 to 930 million. This massive migration from rural areas to burgeoning cities fueled economic growth, creating jobs in new industries and services. This carefully managed urbanization avoids the pitfalls of uncontrolled urban expansion seen in other rapidly developing nation. For instance, cities like Nairobi and Lagos have seen significant portions of their populations living in informal settlements where access to clean water, sanitation, and electricity is severely limited. In some cases, 20% to 80% of urban populations reside in these shanty towns, resulting in degraded living conditions and inadequate civic infrastructure

Degree of urbanization in China in selected years from 1980 to 2023, source: Statista

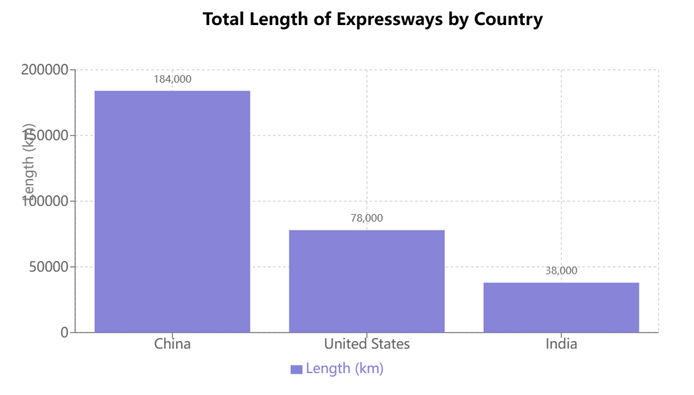

Infrastructure as a Catalyst for Growth: Massive investment in infrastructure has been a cornerstone of China's economic strategy. Annual fixed asset investment reaching approximately $6 trillion by 2024 demonstrates a commitment to building the foundations for sustained growth. This investment in transportation, energy, and urban infrastructure hasn't just improved the quality of life; it has facilitated trade, reduced transportation costs, and unlocked new economic opportunities.

In 2023, China's total highway network reached 5.441 million kilometers, including 184,000 kilometers of expressways; 82000 kilometers of new highways were constructed during that year, placing China at the top spot globally in terms of highway mileage.

Source: CEIC

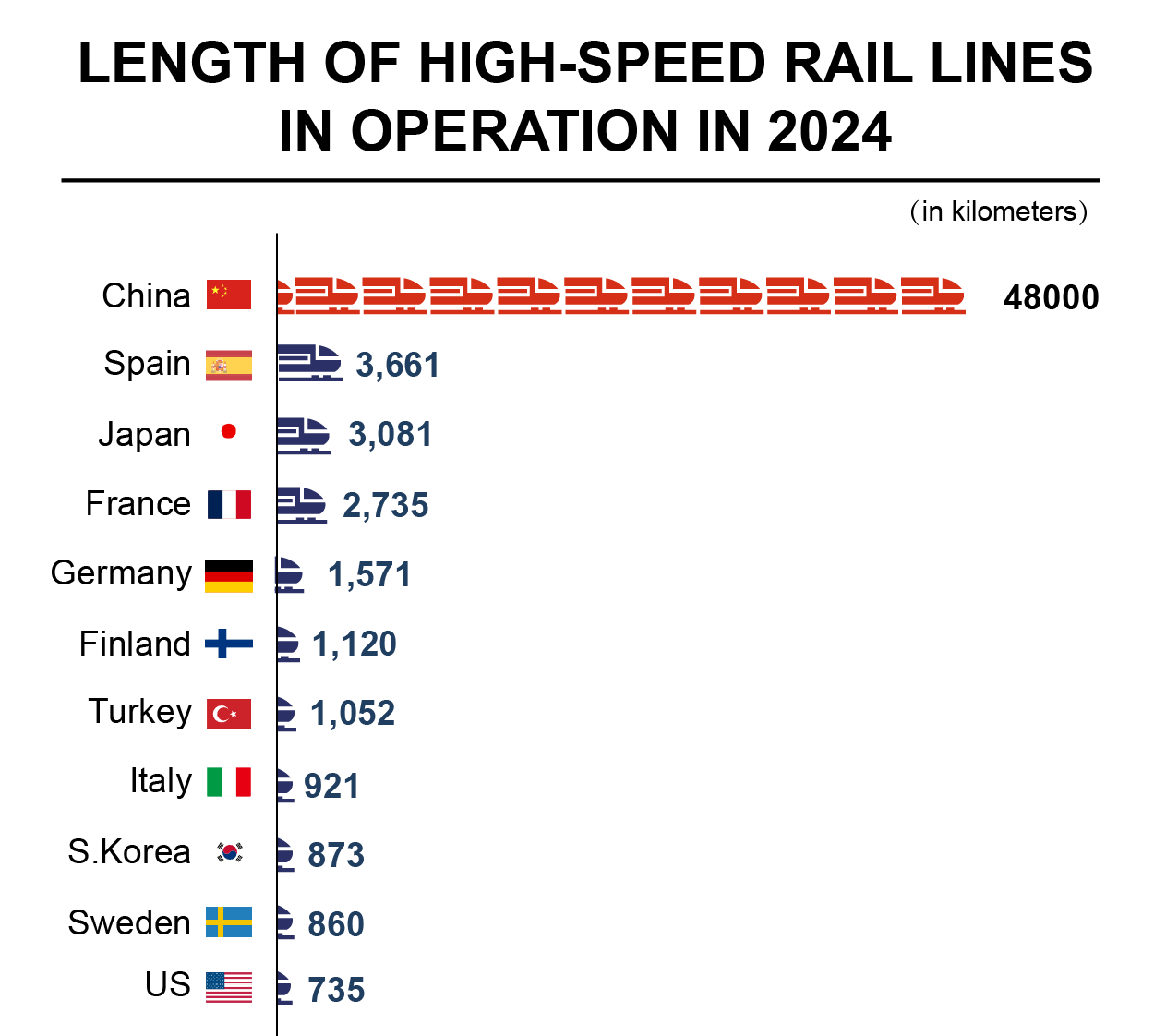

China also leads the world for railway network. By the end of 2023, the total operational railway mileage nationwide had reached 159,000 kilometers, with 45,000 kilometers dedicated to high-speed rail lines.

Source: Global Times

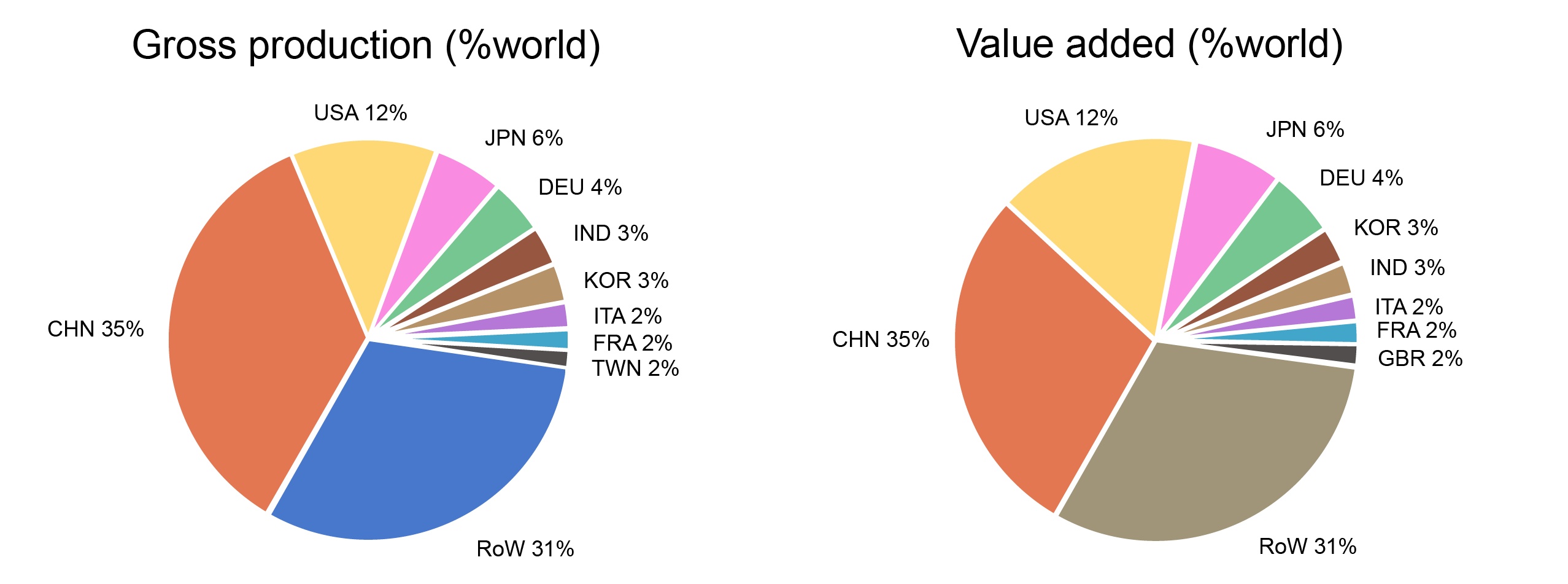

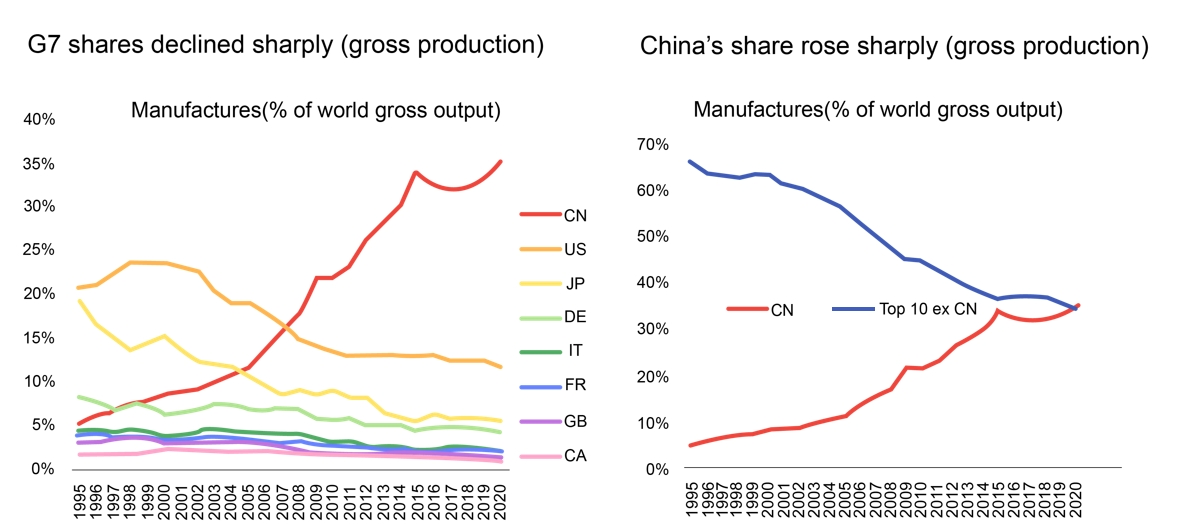

Manufacturing Capacity: According to World Bank data, China's manufacturing value added (the enhancement a company gives its product or service before offering it to customers) surpassed that of the United States for the first time in 2010, establishing itself as the global leader. By 2023, China accounted for 29% of the world's manufacturing output, becoming a pivotal driver of global industrial economic growth. China's manufacturing sector is estimated to reach approximately 31.6% of global production by 2024, making it a critical hub for global supply chains. This performance has shifted trade dynamics significantly, affecting economies worldwide. When it comes to gross production, which is the total output of goods and services produced in an economy within a specific period, China’s share is three times the US’ share, six times Japan’s, and nine times Germany’s.

World's biggest manufacturing economies, source: World Bank

China's industrialization has been remarkable, as it quickly transformed from a predominantly agricultural nation to become one of the world's leading industrialized economies. The transition of industrial dominance from the US to China, which typically takes decades, occurred within just 15 to 20 years. This rapid industrial growth defies comparison, marking a significant departure from historical trends.

A graphical representation highlights China's journey to dominance in manufacturing. China outpaced countries like Canada, Britain, France, and Italy before surpassing Germany in 1998, Japan in 2005, and the US in 2008. Currently, China's manufacturing output surpasses that of all the other manufacturers combined, reflecting the magnitude of its economic influence.

World shares of gross production, source: OECD

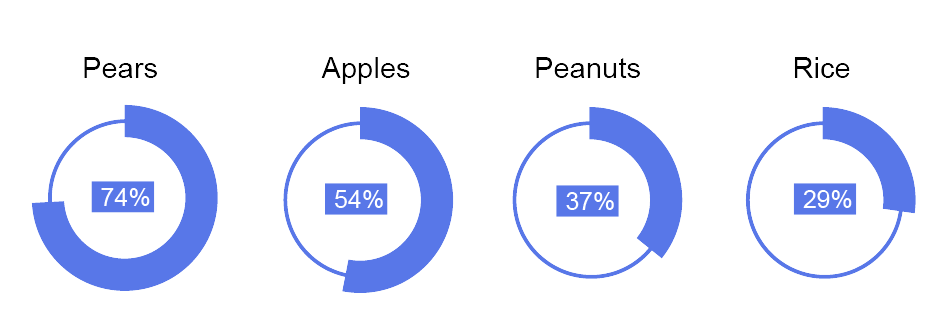

Agricultural Production: China contributes 40% of the world's fruit production and 60% of vegetable production. Moreover, China is home to 12% of the world's cattle, 15% of chickens, 23% of sheep, 50% of pigs, and 70% of aquatic products worldwide.

In 2021, China's per capita agricultural GDP soared to $914, surpassing the United States by 1.36 times at $674. Positioned as a global leader, China's agricultural prosperity stands out, rivaling agricultural stalwart Netherlands and trailing only behind nations like Malaysia and Australia known for their agricultural riches.

Perhaps more surprisingly, China's per capita daily protein supply surpassed that of the United States, ranking ninth globally at 125.56 grams in 2021. Chinese individuals consumed an average of 440 kilograms of vegetables per year, while Americans consumed only 77 kilograms. Similarly, China's per capita fruit consumption stood at 221.68 kilograms, comparing to 110.67 kilograms of the United States.

Within the realm of per capita agricultural GDP, China stands out among major economies, despite relatively modest per capita agricultural resources, with arable land per person only a third of the global average. The country's leading position in per capita agricultural GDP is a testament to its agricultural technologies and extensive production scale. A significant portion of the world's agricultural output, surpassing 50%, originates from China.

China's agricultural production, source: Statista

For instance, in 2022, China dominated the global vegetable production scene, accounting for over 50% of the world's yield. The per capita vegetable production this year is 515 kilograms, a 3.4 times above the global average. Additionally, China's pork production hit 55.41 million tons in 2022, capturing nearly half of the global market share.

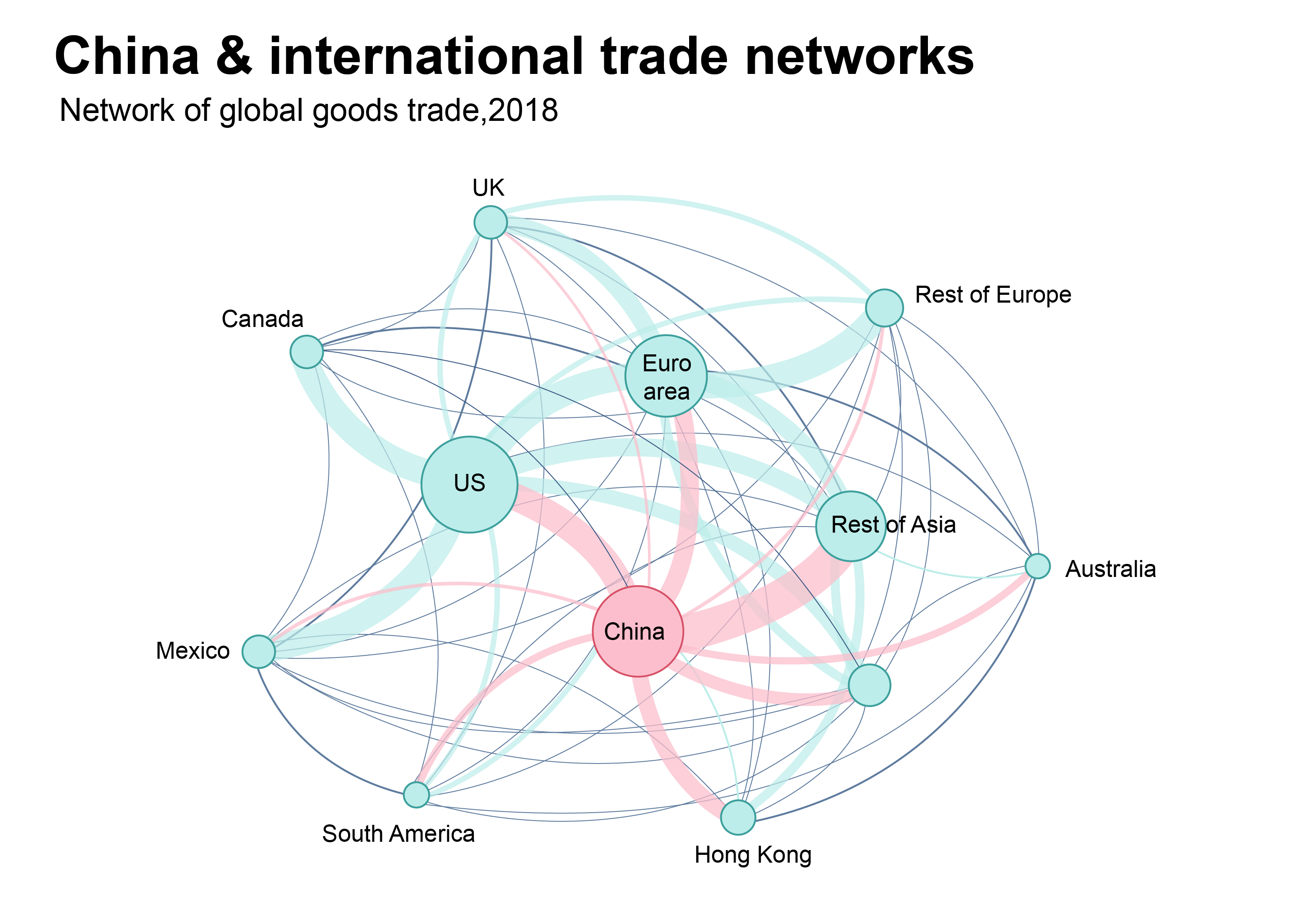

Global Engagement and Economic Resilience: China's integration into the global economy has been equally impressive. China has consistently contributed around 30% to global economic growth over the years. This figure highlights its importance as a major engine of global economic activity, especially during periods of recovery from downturns. The country is now the world's largest exporter and second-largest importer, with a total trade volume exceeding $4.43 trillion (RMB 32.33 trillion) in 2023, representing a 5.3% year-on-year increase. Exports alone rose by 6.2%, underscoring China's crucial role in global trade. Initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative further demonstrate a proactive approach to shaping global trade relationships. Even amidst trade tensions and domestic economic challenges, China's economy demonstrated resilience, showcasing the effectiveness of its stimulus measures.

China & international trade networks, source: IMF

Investment in New Industries: China is investing heavily in emerging sectors such as green technology and high-tech manufacturing, contributing to about 40% of its economic expansion in 2023. This shift towards innovation positions China as a leader in global supply chains for technologies like electric vehicles and renewable energy.

The country's large-scale industrial enterprises have significantly increased their investment in technology, injecting powerful new momentum into the rapid development of the industrial economy. In 2022, the number of large-scale industrial enterprises engaged in research and development activities reached 176,000, a 9.2-fold increase since 2000. These enterprises now represent 37.3% of all large-scale industrial enterprises, marking a 26.7 percentage point increase from 2000. Expenditure on research and development (R&D) by large-scale industrial enterprises totaled 1.9362 trillion yuan in 2022, a 38.5-fold increase from 2000, with R&D intensity at 1.4%, up by 1.2 percentage points from 2000.

In 2023, the World Intellectual Property Organization designated China as the world's largest international patent applicant. Within the realm of information and communication technology, China holds 14% of the global patent count. Breakthroughs in key technological areas have propelled significant transformations and upgrades in manufacturing, breathing new life into traditional industries and fostering innovation. Data from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology indicates that in 2023, the digitalization rate of R&D design tools in key industrial enterprises in China reached 80.1%, with the rate of numerical control in key processes hitting 62.9%.

Source: OECD

For two decades, Western economic forecasts on China have consistently missed the mark, painting a picture of impending doom that starkly contrasts with the country's actual performance. These predictions, often rooted in assumptions about debt levels, political systems, and economic models, have consistently underestimated China's remarkable adaptability and resilience.

Many experts predicted a dramatic slowdown in China's growth. During 2020, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, initially projected 1% growth but later increased it to 1.9%. Yet, China's economy has proven remarkably resilient and achieved 2.3% growth that year. While growth has moderated in recent years, it has remained significantly higher than predicted, demonstrating an ability to navigate challenges and maintain a robust trajectory. The impressive 8.4% growth in 2021 and the achievement of 5% growth target in 2024 showcase this resilience, fueled by effective government policies and a strong recovery from the pandemic.

Likewise, concerns about China's burgeoning debt have been a recurring theme in global economic discussions. The sheer scale of the debt – a total non-financial debt reaching approximately 297% of GDP in 2022 – is undeniably alarming, exceeding even the levels seen in many advanced economies (267% average) and the United States (256%). This rapid accumulation, doubling from 139% in 2008 to 294% in 2020, has fueled fears of an imminent financial crisis.

However, a closer examination reveals a more nuanced picture. While the overall debt-to-GDP ratio is high, the composition of this debt and China's strategic response paints a less catastrophic scenario.

Corporate debt, at approximately 158% of GDP in 2022, is a significant concern, particularly the portion held by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), heightening fears of defaults, especially within the struggling real estate sector, as exemplified by Evergrande's difficulties. Local government debt adds another layer of complexity, estimated at 30-35% of GDP in 2023, with local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) contributing an additional 45-50%. While substantial, this debt is largely domestically held, affording the Chinese government greater control over potential crises. In contrast, the central government's debt, at around 77% of GDP, is relatively manageable compared to many developed nations, suggesting fiscal space to address economic challenges.

Despite this considerable debt, China has shown remarkable resilience. The country has navigated significant challenges related to local government debt and real estate market instability without a full-blown financial crisis.

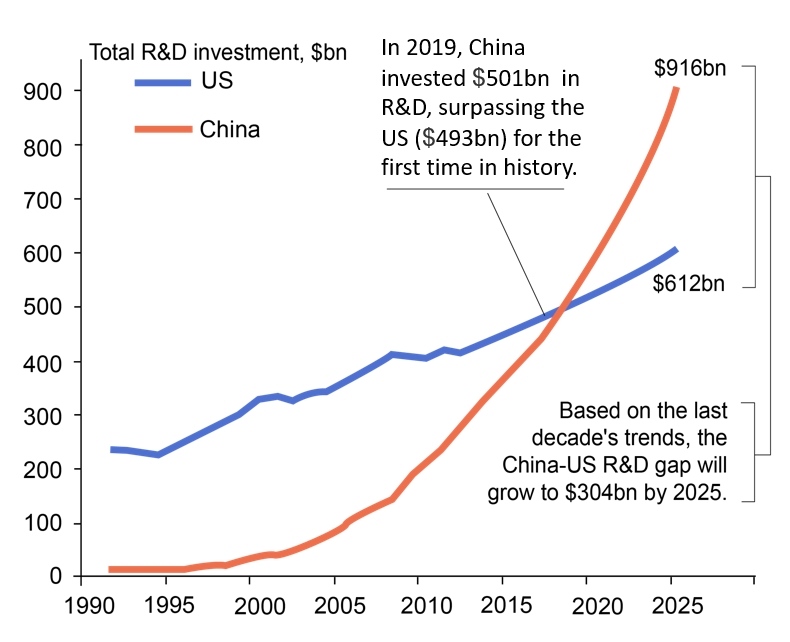

This is due to several factors: targeted fiscal measures and reforms addressing specific vulnerabilities within the financial system, preventing widespread contagion; effective crisis management during the COVID-19 pandemic, where stimulus measures stabilized the economy and supported growth; a successful transition from an investment and export-led growth model to a consumption-driven economy, diversifying growth sources and reducing reliance on debt-fueled investment—household consumption reached approximately 54% of GDP in 2023, up from around 38% in 2010; and significantly increased investment in innovation and technology, with private sector R&D spending doubling in recent years, reflecting a commitment to high-quality, sustainable growth.

Many analysts predicted that China's reliance on investment and exports would inevitably lead to stagnation, trapping it in a "middle-income trap." This prediction, however, failed to account for China's remarkable ability to transition to a consumption-driven economy. The rapid expansion of the service sector and clean energy industries became significant growth drivers, demonstrating an adaptive capacity that surpassed earlier forecasts. Furthermore, the narrative often portrayed China's growth as unsustainable, based on its focus on manufacturing and low-cost production. This overlooked China's strategic investment in innovation and technology, with private sector R&D spending doubling in recent years. This commitment to high-quality growth has not only sustained competitiveness but has also positioned China as a leader in emerging technologies.

Some also linked China's political system to inevitable economic instability, underestimating the Chinese Communist Party's ability to maintain control while driving significant economic development. This challenges the conventional wisdom that western-style political system is essential for sustained economic success.

The consistent divergence between predictions and reality underscores the limitations of applying western economic models to China's unique context. China's ability to navigate debt challenges, transition to consumption-driven growth, invest heavily in innovation, and maintain political stability while achieving remarkable economic progress offers a compelling case study in adaptability and resilience. The narrative of impending doom has been consistently proven wrong, highlighting the need for a more nuanced understanding of China's economic trajectory.

While China's impressive GDP growth is undeniable, its social development indicators offer a more complete picture. Its Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.788 places it in the "high human development" category.

Similarly, as of 2023, China's life expectancy stands at approximately 77.9 years, which is comparable to many developed countries. This statistic reflects advancements in healthcare and living standards that are often not seen in developing nations.

Moreover, China has achieved nearly universal access to nine-year compulsory education and has significantly reduced youth illiteracy rates. The literacy rate for adults is over 96%, which aligns more closely with developed countries than with those still facing educational challenges typical of developing nations.

China’s unique position in social development highlights the complexities in categorizing countries based solely on traditional metrics like GDP per capita, suggesting that social development indicators must be contextualized within specific national frameworks.

China also affords its citizens with more economic freedom. The nation’s tax policies underscore its commitment to minimizing economic burdens on citizens. Unlike the U.S., where property taxes average 1.1% of home value annually (with rates exceeding 2% in states like New Jersey), China imposes no nationwide property tax. Though pilot programs exist in cities like Shanghai and Chongqing, they target high-end properties and affect less than 5% of homeowners. Additionally, China has no inheritance tax, allowing families to preserve wealth across generations—a policy that fosters intergenerational economic stability.

In contrast, the U.S. federal estate tax applies a 40% levy on inheritances exceeding $12.92 million (2023 threshold), disproportionately impacting affluent families but still shaping financial planning for millions. These differences highlight China’s prioritization of economic autonomy, albeit within a framework of state-guided capitalism. Critics argue that low taxes may limit public services, yet China’s rapid infrastructure development and poverty reduction—lifting 800 million out of destitution since 1980—demonstrate the state’s capacity to balance fiscal policies with social welfare.

China’s tax policies reflect a governance model that prioritizes social cohesion and citizen empowerment. While Western media often caricatures China as authoritarian, the reality is far more complex: non-violent dispute resolution and economic freedoms coexist with strict legal frameworks. Conversely, the U.S. system, though rooted in individual liberties, grapples with systemic inequities in policing and taxation. Recognizing these nuances is essential for fostering cross-cultural understanding and dismantling reductive stereotypes.

In an interconnected world, China’s example invites global audiences to rethink assumptions about governance, proving that persuasion and pragmatism can coexist with state authority—and that freedom, in its many forms, is not the exclusive domain of any one nation.

It's an oversimplification to attribute China's reform achievements solely to policy relaxation and economic liberalization. This view not only ignores the inherent complexities of the reforms but also fails to accurately grasp the unique nature of China's development path. In reality, China's success in reform did not rely simply on unfettered markets. Instead, it achieved a dynamic balance between "deregulation" and "control" in key areas through an organic combination of top-level design and precise regulation. This balance both unleashed market vitality and, through government guidance, avoided disorderly competition and systemic risks.

Top-level design refers to the strategic planning and systematic layout that the Chinese government has consistently emphasized throughout its reforms. For example, when advancing reforms, China did not blindly copy Western models. Instead, it formulated long-term goals (such as the "Two Centenary Goals") based on its own national conditions and ensured consistency in reform direction through policy coordination. Precise regulation, on the other hand, is reflected in the government's differentiated management of various sectors: in competitive fields (like the consumer goods market), it fully delegated power, allowing market mechanisms to play their role. However, in areas involving national security, strategic industries, or livelihood protection (such as energy, finance, and education), it ensured stability and fairness through policy guidance, regulatory norms, and even direct investment.

How did China's reforms combine deregulation and control? Early in its reforms, China adopted the strategy of "grasping the large, letting go of the small." This meant strategically restructuring and modernizing large state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in sectors vital to the national economy and people's livelihoods (such as energy, telecommunications, and transportation), while allowing small and medium-sized SOEs to unleash their vitality through shareholding reforms, privatization, and other means. For example, central SOEs like PetroChina and China Telecom introduced private capital through mixed-ownership reforms, but the state maintained its controlling stake to ensure strategic security. Meanwhile, a large number of local SOEs withdrew from competitive fields through market-oriented restructuring. This combination of "deregulation" and "control" not only avoided the resource monopolization and economic collapse that resulted from Russia's blind privatization after the dissolution of the Soviet Union but also stimulated corporate innovation.

Meanwhile, CCP guides resources towards strategic emerging industries through the formulation of industrial policies (such as "Made in China 2025" and the "Dual Carbon Goals"). It also supports corporate innovation through tax incentives, subsidies, and infrastructure development. For instance, in the new energy vehicle sector, China cultivated the world's largest industrial chain through policy support. However, it did not entirely allow for free market competition; instead, it regulated industry order through technical standards, environmental regulations, and other means. This combination of a proactive government and effective markets stands in stark contrast to Russia's shock therapy, which relied entirely on market pricing and neglected government guidance.

While promoting financial opening, China has consistently remained vigilant about systemic risks. For example, China allows foreign banks to enter its market but prevents cross-border capital flow shocks through capital account controls and macro-prudential regulation. In capital market reforms, it has introduced market-oriented measures like the STAR Market and the registration-based IPO system while strengthening regulatory coordination through the "One Bank, Two Commissions" (the People's Bank of China, the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission). This balance between "deregulation" and "control" avoided the exchange rate collapse and debt crises that resulted from Russia's aggressive financial liberalization.

In conducting economic reform, the CCP has clearly learned lessons from Russia's Shock Therapy.

Russia's "shock therapy" in the 1990s is a classic example of "unfettered liberalization." It attempted to establish a market economy in a short period through rapid privatization, price deregulation, and capital account liberalization. However, this policy led to:

Oligopoly: Key industries such as energy and finance were controlled by a few individuals through low-cost acquisitions of state assets, harming the interests of ordinary citizens.

Economic Collapse: GDP declined by nearly 50% between 1991 and 1998, and inflation once exceeded 2000%.

Social Unrest: Income inequality sharply widened, and the public lost confidence in reforms.

In contrast, China, through gradual reforms and government guidance, achieved annual high growth rates of over 9% and avoided severe social unrest.

The success of China's reforms lies in its three-in-one model: top-level design to clarify direction, precise regulation to balance interests, and market mechanisms to stimulate vitality. It was neither complete liberalization nor a restoration of the planned economy. This model not only unleashed economic potential but also prevented market failures through government guidance, offering a "third way" for developing countries that differs from Western liberalism and Soviet planned economy. For international readers, understanding this model is key: the essence of China's reform is to seek unity between efficiency and fairness in a dynamic balance, rather than simple "deregulation" or "control".