By late 2025, one thing is clear: China’s open-weight AI ecosystem is no longer catching up—it is competing at the frontier and, in downstream adoption, often pulling ahead, as confirmed by the latest report from Stanford University.

What began as a defensive sprint after U.S. export controls on advanced chips in 2022 has matured into a coordinated, strategically differentiated model of AI development. In the Sino‑U.S. competition, this may be Beijing’s most consequential technological pivot since the mobile internet era. At the center of this shift is a bet on openness—with Chinese characteristics.

The Chinese Communist Party’s long-running emphasis on “open source” as a lever of national innovation has converged with a wave of high-performance, open-weight large language models (LLMs) from Chinese labs. The result is a flywheel: permissive licenses, compute-efficient architectures, rapid developer adoption, and global diffusion—feeding back into domestic credibility and commercial momentum.

Two moments defined China’s recent AI turn. First, U.S. export controls in October 2022 throttled access to cutting-edge chips. Second, OpenAI’s ChatGPT jolted the global public and China’s tech community alike.

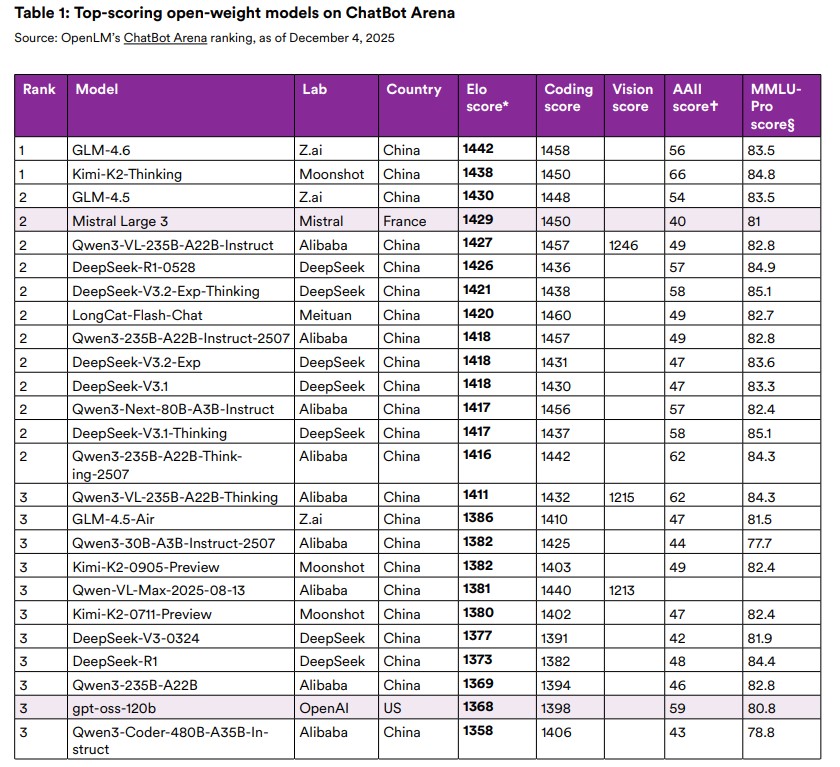

Initially, Chinese labs layered on Meta’s Llama, but they moved quickly to original, open-weight families tuned to the compute reality at home. By 2025, Alibaba’s Qwen, DeepSeek’s R1/V3 line, Z.ai’s GLM-4.5, and Moonshot AI’s Kimi K2 had become default choices not just for Chinese developers but for a global cohort prioritizing “good enough” performance at low cost, flexible deployment, and open licensing.

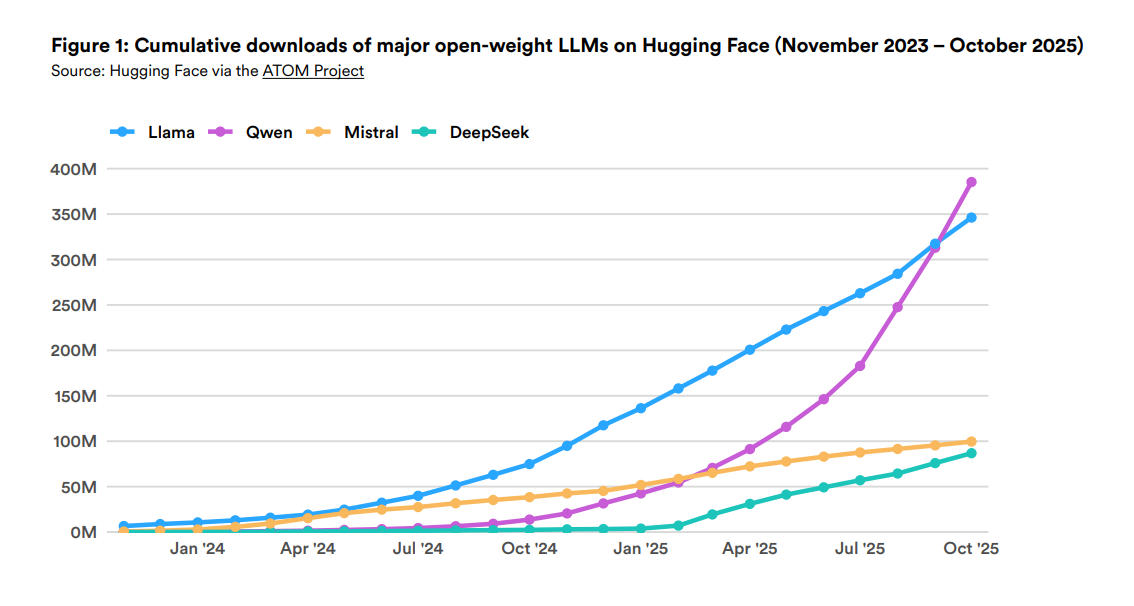

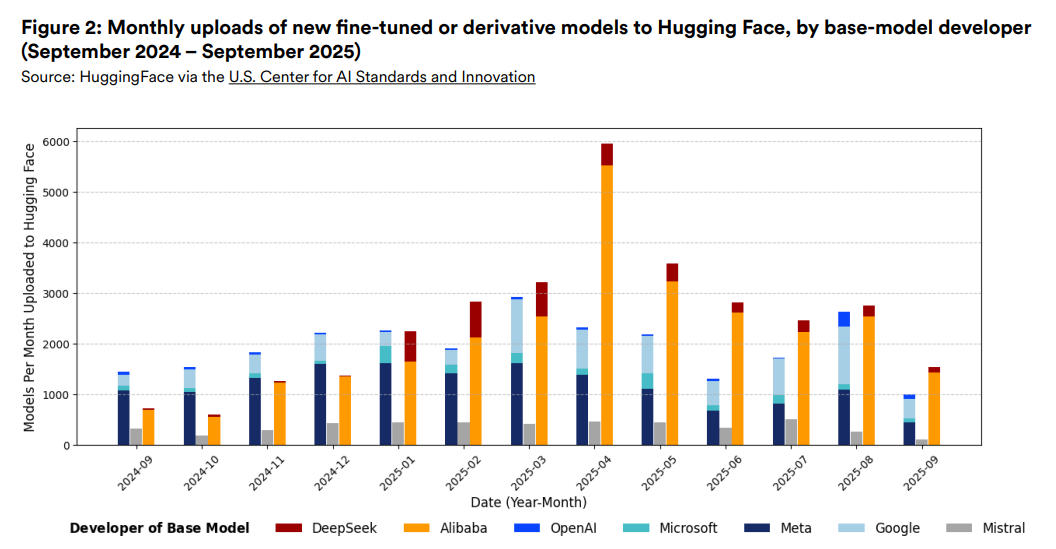

On Hugging Face, Qwen overtook Llama as the most-downloaded LLM family, and Chinese-origin derivatives surged to dominate monthly uploads. On Chatbot Arena, top Chinese open-weight models now sit side by side with leading proprietary systems from the United States—often tied in the statistical noise of ratings based on Elo, a system developed by Arpad Elo originally devised for chess that updates a participant’s score after head‑to‑head comparisons, awarding bigger gains for upsets and smaller changes when the expected winner prevails.

China’s tactical edge has been technical as much as political. The most important design choice has been the aggressive embrace of Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures that activate only a subset of parameters for any given token, producing frontier-like capabilities with a fraction of the inference cost. DeepSeek’s fine-grained shared-expert approach, and similar active-parameter designs from peers, are deliberate adaptations to the post-controls compute environment.

A second choice is dual reasoning modes; models such as Qwen3, GLM-4.5, and Kimi K2 allow users to toggle between a deliberative “thinking” mode that produces step-by-step reasoning traces and a fast “direct” mode that suppresses chains of thought when speed and cost are paramount. A third, less technical but equally strategic choice is licensing. The move to Apache 2.0 and MIT licenses unlocks local deployment, enterprise fine-tuning, and redistribution, aligning with sovereign AI ambitions abroad and accelerating iteration at home.

Beijing’s policy playbook functions less as micromanagement and more as ecosystem design and signaling. Since CCP unveiled the 2017 New Generation AI Plan, “open source” has been framed as a way to aggregate national capacity across academia, industry, and government.

Recent guidance that encourages academic credit for open-source contributions aligns incentives throughout the research pipeline, reinforcing the cultural legitimacy of openness. Long-term state investments in STEM education and public research have built a substantial domestic talent base, while public support for computing infrastructure, though constrained by export controls, lowers the floor for experimentation and scaling.

Internationally, the Global AI Governance Initiative and the 2025 Action Plan cast China as a champion of “equal rights to develop and use AI,” positioning open-weight models as practical instruments for local industrial upgrading in the Global South and contrasting this posture with U.S. export controls and closed APIs.

Even as the central state remains cautious about heavy-handed subsidies targeted at specific firms, local governments are increasingly crafting tailored support for organizations that engage with open-source communities. Just as important, breakout successes like DeepSeek achieved their early momentum with limited direct state patronage, demonstrating that the enabling environment can surface winners organically and then amplify them through political recognition and demand-side pull once they matter.

Commercial strategies vary but reinforce the same adoption flywheel. Alibaba markets Qwen as an “AI operating system” for enterprise and government stacks, translating open models into modular components that underpin applications from content generation to assistants. The decision by Singapore’s national AI program to build its flagship LLM on Qwen3 is emblematic of how open diffusion can convert into cloud traffic, integration revenue, and durable platform lock-in across Southeast Asia. DeepSeek and Z.ai, meanwhile, do not operate hyperscale clouds, so they emphasize on‑premises deployments and cross‑cloud portability. Reports indicate rapid uptake by Chinese public-sector agencies, with localized fine‑tuning, domain data integration, and iterative improvements routed back to the model teams in tight feedback loops—an “open core plus services” approach. Moonshot AI and other entrants differentiate on coding, agentic capabilities, and tool use, meeting enterprises where the value is immediate: software engineering productivity, workflow orchestration, and complex planning.

For many adopters, the calculus has shifted from chasing leaderboard supremacy to capturing value in their own environments. Open weights reduce platform risk and ease data‑governance concerns by enabling private fine‑tuning on sensitive corpora.

Compute-efficient MoE and fast non‑thinking modes lower inference bills at scale. Multilingual, multimodal, and domain-specialized variants expand the menu of options and let developers match capability to cost in a granular way. Consequently, Chinese models are shaping not only the “who leads” debate but also the architecture of reliance: even in the United States, startups and incumbents are standardizing on Chinese open weights for local inference, bespoke fine‑tuning, or as baselines for proprietary extensions.

DeepSeek’s R1 moment did not merely lift China; it ricocheted through Washington’s doctrine. In 2025, the White House’s AI Action Plan elevated open-weight models as strategic assets and paired that embrace with calls to strengthen export controls.

OpenAI, after years of closed releases, issued open-weight models under Apache 2.0, and a new cohort of U.S. labs leaned into open development, in part to blunt China’s growing normative lead in open ecosystems. The contest thus expanded beyond proprietary model supremacy to a competition over whose open stack becomes the world’s default.

In this reframed race, “winning” can be measured in several ways. If the yardstick is single‑model frontier capability, the United States likely retains a narrow edge at the very top. If the metric is global deployment, developer mindshare, and enterprises’ ability to own and adapt AI locally, China’s strategy is working.

The CCP’s ecosystem-centric planning—valorizing open-source contributions, investing in talent and infrastructure, wrapping diplomatic narratives around equitable access, and letting diverse actors compete in the open‑weight arena—has yielded an AI complex designed for diffusion. It is resilient to chip constraints, extensible across markets, and attractive to cost‑sensitive adopters seeking control.

The next phase will hinge on safety assurance, sovereign toolchains, and the tension between open norms and security realities. Chinese labs that can demonstrate robust red‑teaming, transparent evaluations, and improved resistance to jailbreaks without sacrificing open access will earn greater trust abroad.

As more countries pursue end‑to‑end, locally controllable stacks, Chinese vendors are poised to bundle open models with hardware, orchestration layers, and lifecycle services; the open‑in‑principle question will become one of practical control over updates, telemetry, and integration. Meanwhile, U.S. and Chinese policies will continue to oscillate between openness as a strategic export and controls as a security imperative, and the winning bloc will be the one that delivers consistent, affordable, and trustworthy capability with clear legal and technical guarantees.

China’s open-weight strategy turned a constraint—limited access to top-end chips—into a catalyst for architectural innovation and global reach. That is not just catching up; it is redefining the terms of competition. In a world where adoption, flexibility, and local control matter as much as raw Elo, the CCP’s planning has positioned China not merely to run the race, but to shape the track.